Words by Emma Warren

Sound designer Aaron Guice needed to find a way to connect with his dad when he was caring for him through Alzheimer’s. They had a shared interest in electronics and sound, which meant that modular synths offered an unexpected solution to the problems of communicating with someone with dementia. It was a highly personal response to a family situation, which has now evolved into AFRORACK – an audio arts organisation that connects children and young adults of colour to modular synths and sound design tools. It began in Chicago in 2016 and has now spread worldwide, with a new base in London.

Guice had been working in LA making commercial sound design for film and TV when his dad became ill, and he returned to his home city of Chicago to act as his carer. “We used modular synths as this way of solving problems and connecting his mind back to reality,” he explains. “He was a brilliant guy – an engineer, a plumber, and he played cello – so playing modular synths allowed him to tap into a lot of his talents. It combined all those things.” They did it like a game: patching, trying to make new sounds and compositions: “We were problem-solving and being creative.”

Mr Guice Snr wasn’t the only inspiration for AFRORACK. Aaron’s mother was an educator for over three decades, working mostly with younger children. “She did something called Science On Wheels which was before the thing we now call STEM,” says Guice. “She was doing this during the Eighties and Nineties, going around from school to school with these kits and concepts where you can easily explain science and engineering topics.” He started running workshops in Chicago, in record stores, museums and at after school facilities, reaching over 1,600 children and young people.

It’s just wonderful to be part of something I truly believe will shape a whole new generation.

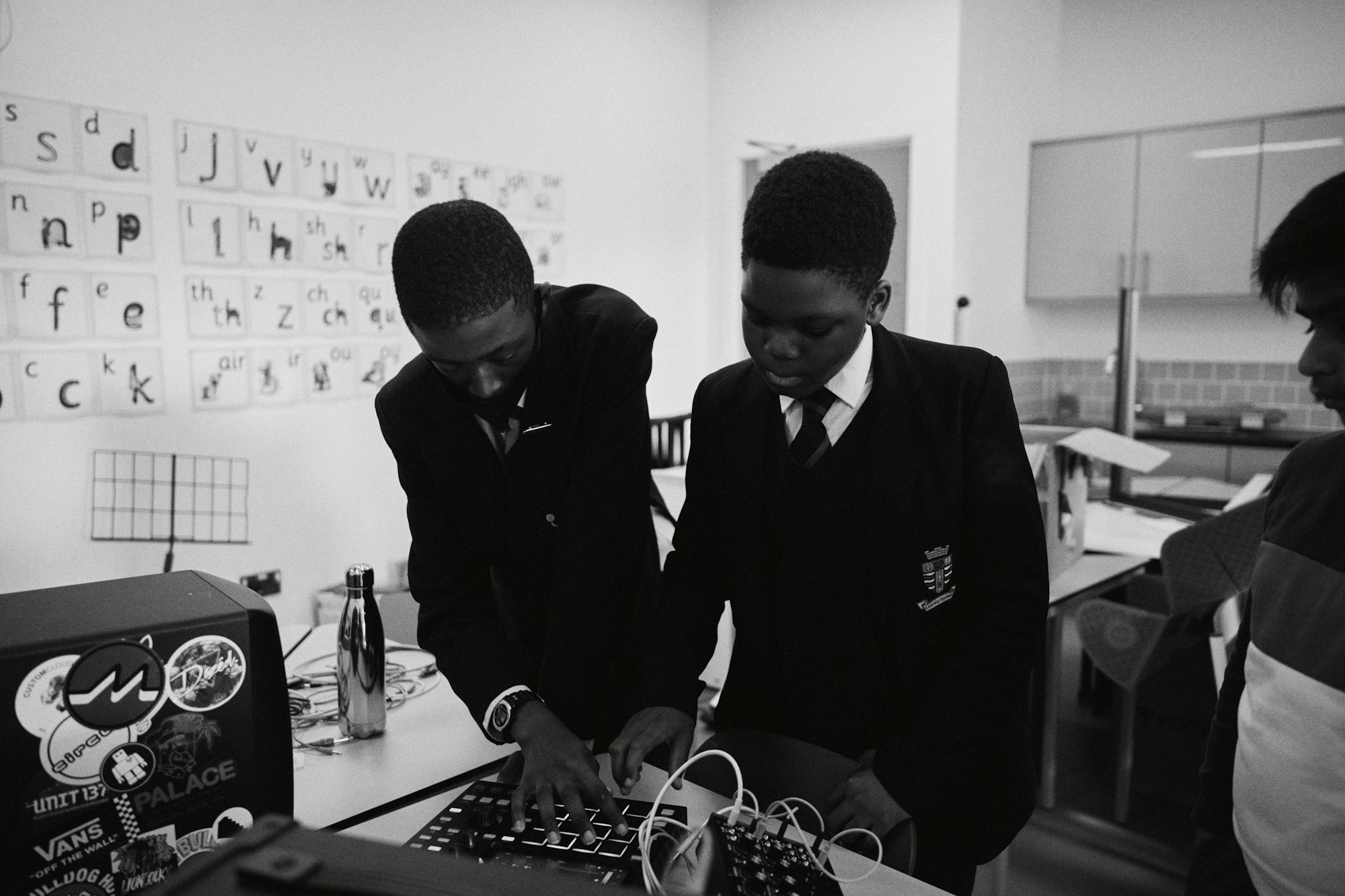

This summer he was in London. The trip included a workshop at Woolwich Creative Club, a free after-school music provision for children and young adults who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access lessons or the opportunity to play together, and where top London trumpeter Byron Wallen is one of the tutors. AFRORACK laid out a bank of Moog DFAMs and MPCs and invited the kids to get involved. Some children were tentatively patching yellow cables from one machine to another, others were huddled around the drum machines, testing out what it felt like to make beats and others still were just looking on, trying to understand how AFRORACK had landed in this south London primary school classroom with the kind of kit you’d usually only see in a research facility or a top-flight studio. “There was a kid who was asking a lot of questions,” remembers Guice. “‘Where’s AFRORACK based, how can I join, what does the name mean?’ I told him about Eurorack and the importance of the re-appropriation of that word. Kids are smart. They know how to pull knowledge out of a lot of stimulus.”

Giving children a playground of synthesisers where they can literally do nothing wrong, he says, is ‘amazing’. “Some kids were afraid to make the wrong choice, thinking it would explode, other people were afraid to touch it. They’re taught from an early age – don’t touch that thing, it’s expensive, put it down. There’s a moment where I had to pick up the synthesiser and drop it on the table to disconnect that financial barrier.”

The project purposefully seeks out global majority children to work with, not least because these children are more likely to experience the economic barriers to accessing new technology alongside a higher awareness of the problems that come with breaking expensive items. Synths aren’t just a great piece of technology, says Guice, they’re also a platform to talk about many other things, including identity.

“When I first started, there were very few Black folks using it and I had never seen a photograph of a Black child using modular synths,” he says. “To my knowledge, we have the first set of photographs of Black children coming together to create on modular synthesisers.” The disconnect is especially striking given the importance of synthesisers to Great Black American music, from Stevie Wonder and Brian Jackson using TONTO to the central role of synthesisers in hip hop. “We have to be comfortable not only performing and displaying our talents, but we also have to be comfortable on the other side of creating – developing – so that we can create compassionate objects and technology that can benefit our communities.” Accordingly, the fully-writeable, dry-erase surface synthesiser Sound Sketch is aimed directly at Black and Brown communities. Guice was part of the sound design team for the Alex Epton sound pack Aperture The Stack and a portion of profits from another Epton release – Entropy – are donated to AFRORACK.

It’s about getting out there, more programmes, more workshops, inspiring more people.

A broader reason for the project’s existence relates to the importance of ensuring that modular makers and the broader STEM industries become more diverse. “If people of different demographics and backgrounds don’t experience and get to solve problems within the industry then people may assume there are no problems.”

AFRORACK is based on a framework developed by Guice that he calls Think Modular. “It comes back to the idea of components and putting them back together. It’s about breaking down your circumstances and your reality and being able to make those connections to solve the problems to create new pathways for yourself.” Everything, he says, is modular. “We also say that the future is modular. A practical thing would be networking and connecting people. Being able to break a problem down into small components and being able to analyse them and get rid of the pieces you don’t need to get to the goal you want.”

The programme has expanded to London and Guice has an intention to develop year-round programming. “It’s about getting out there, more programmes, more workshops, inspiring more people. Maybe creating some new products that help heal that divide as well.”

It’s a big ambition, but Guice is also happy with how far AFRORACK has come. “It’s just great to be here. Everyone at home is happy. My mom is happy. To think how far this small idea has come, from just me and my dad, and to share that positive love and energy with Black people around the world has just been incredible. Although it’s a huge responsibility, it’s just wonderful to be part of something I truly believe will shape a whole new generation.”