Words by Emma Warren

Hainbach is sitting in his studio in a position that will be familiar to the 1.5 million viewers who’ve watched one of the videos on his YouTube Channel. We’re talking about cables.

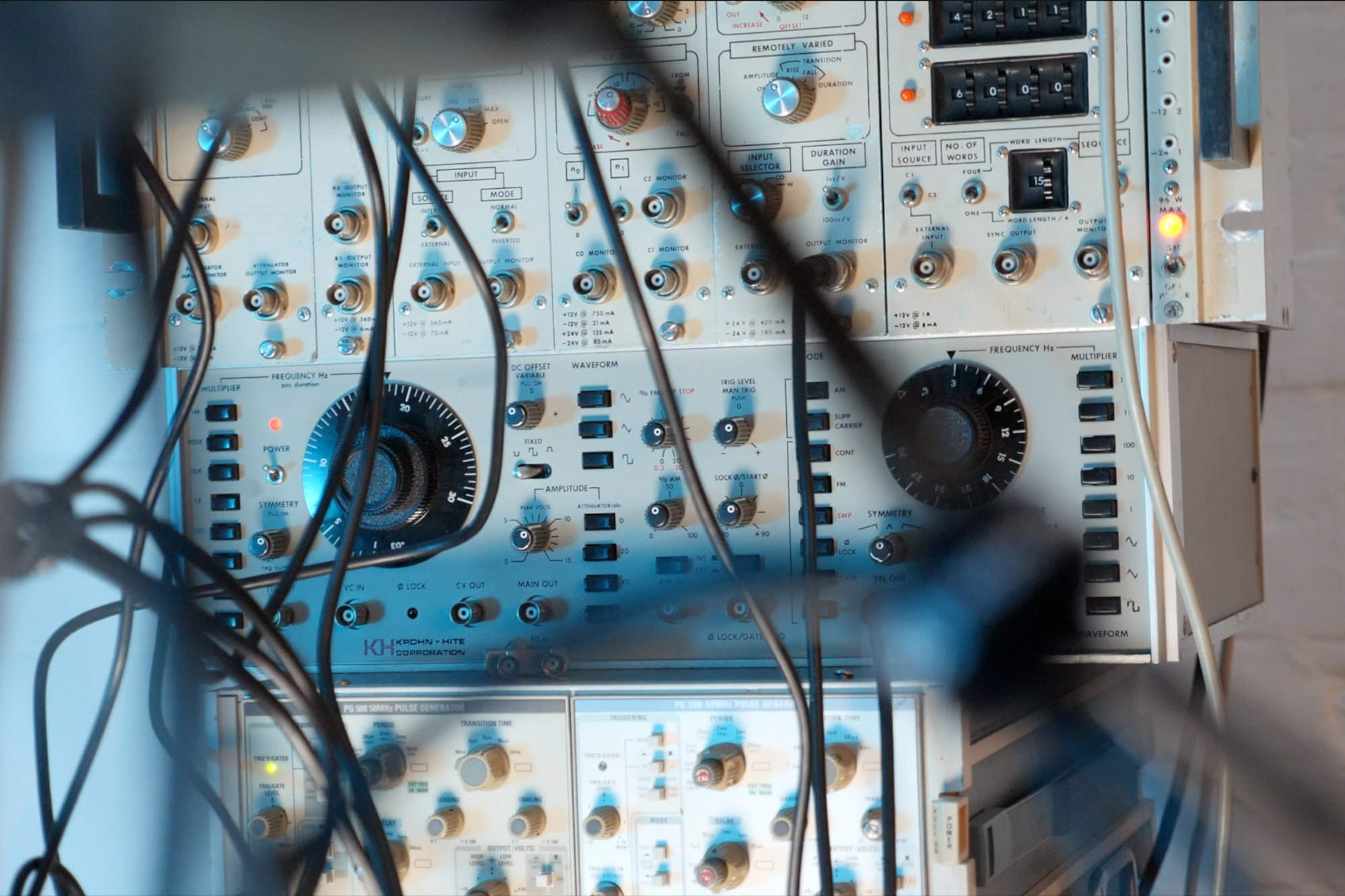

“That’s where the beauty and the complexity happens,” he says. “Oftentimes the magic is not in the different elements in the interconnection, it's how you patch them. With modulars, and even with test equipment, which is a bit less open to be inter patched in that way, you get relationships that are so alive, that minute changes will create drastic results, literally building up this butterfly in the Amazon, creating a hailstorm in New Jersey kind of thing.”

The producer, musician, plug-in developer and soundtrack composer is building his own ‘Noah’s Ark’ of cables, ensuring he’s always got something ready that can link the disparate elements in his beautifully jammed Berlin studio. Some of these came in useful when he built the stacked towers of ancient test equipment that made the sounds on his new release Landfill Totems.

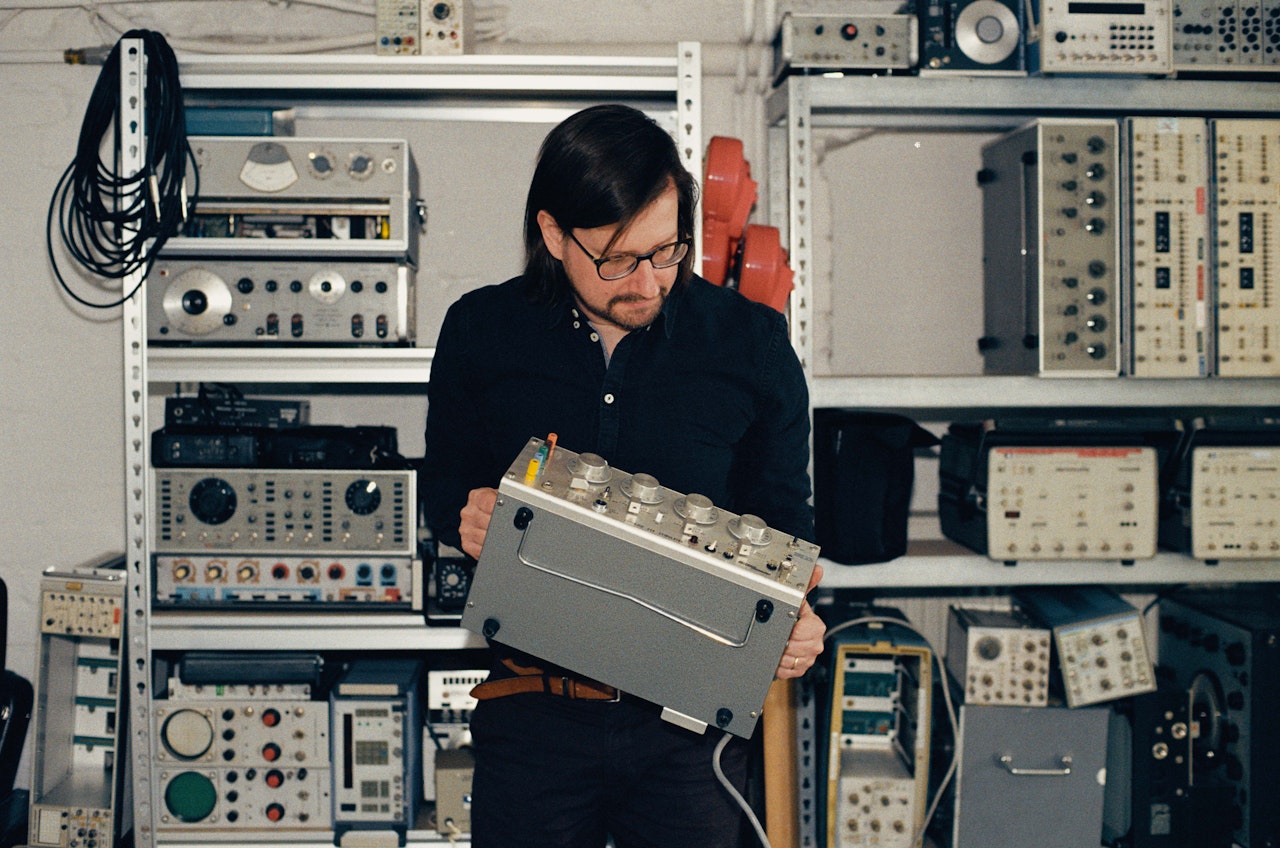

He’d begun buying test equipment and bought a lot of stuff, ‘very fast, very cheaply’ off eBay, local classified ads and from a guy who was clearing out his grandad’s shed. Then he was asked by Berlin art gallery PNDT if he wanted to do a three month residency. “I said perfect! Now I got a storage space!”

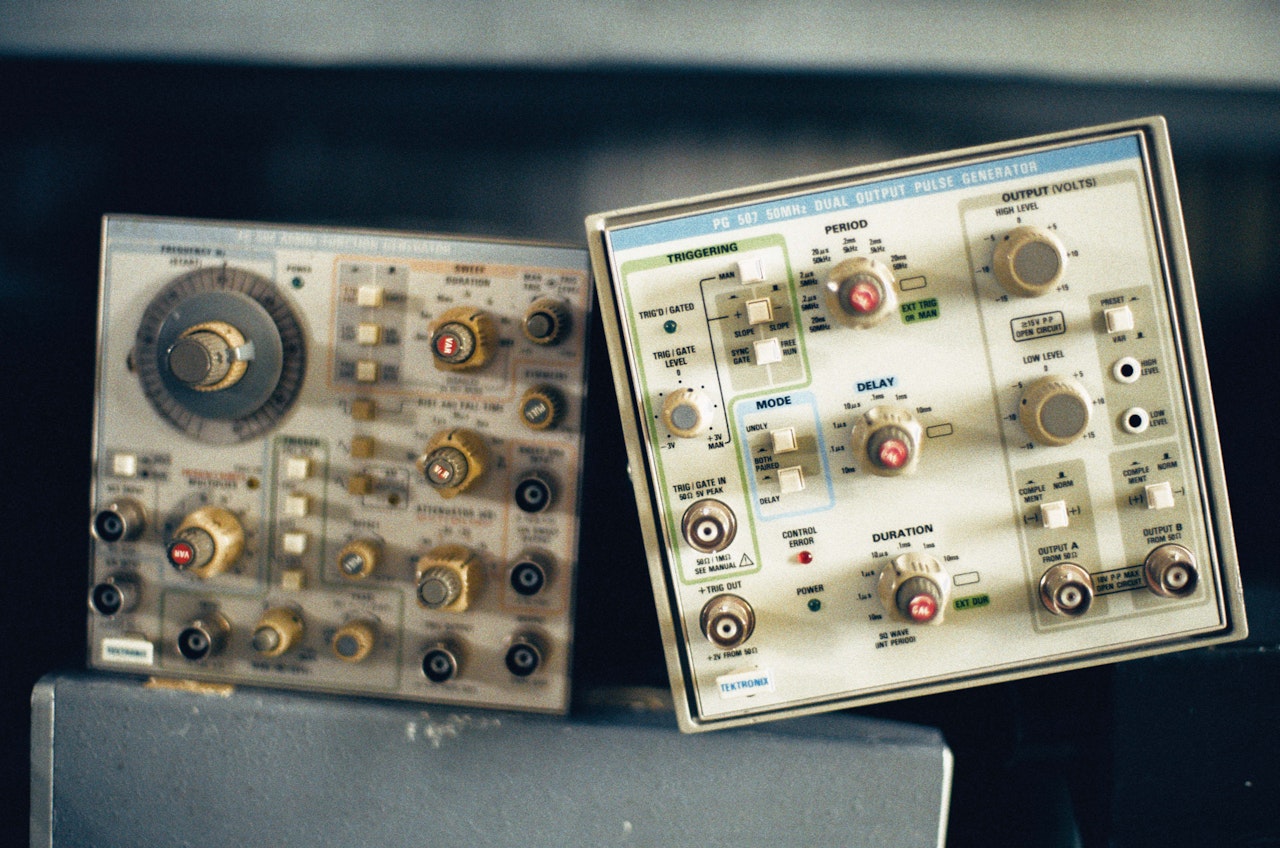

He took a van-load of kit over, put it in the room, and realised that in the vast whiteness of an art gallery, his collection got completely lost – even though it was literally a van-load. So he started stacking machines designed to test telegraph wires and nuclear reactors and out of the stack, a statue appeared. “It had all these faces appearing over it because the test equipment has these little faces and the brain makes you think of a totem because you connect all these different things.”

Some of these things can output crazy voltages. It's easy to get a little shock.

He built the totems in a few hours and then began patching them as instruments. “I couldn’t plan it in the way I would normally plan a composition,” he said. “I wrote a piece by seeing what was available to me.” He played the music at ‘a couple’ of concerts at the gallery.

It was a powerful experience in more than one way. “These things, they look dangerous. And they are probably dangerous, because I never fixed them in any way. So when you would walk past them, they would shake. And, of course, some of these things can output crazy voltages. And it's easy to get a little shock or a bigger shock if you mis-patch something. So it's a bit of a dangerous way of making music, but it's also fun.”

Many of the items died while he was playing or recording them (‘some songs contain the last sounds from these instruments’) and many more would probably have died had he continued playing them out. But then Covid happened and instead, he turned them into an album and sample library for Spitfire Audio titled Landfill Totems. “I don't want this to stop singing, I want them to live on. And I don't want them to lose their purpose and just like rot away in my cellar or something.”

Right now, they are down in his cellar, disassembled and just looking like pieces of gear. “These things were meant to look at photons or launch satellites into space and to check airplane vibrations but they’re completely obsolete with today’s technology. Every time I put them together again it becomes something new.” He pauses. “It just takes forever to set them up.”

He describes working the machines as operating in ‘hard mode’. “High difficulty. Nothing of this was meant for making music. So there is a lot of struggle just to change like the pitch or to do all these things that are really simple on any synthesizer.”

“I'm constantly working with such a minimal amount of signals everything that I can add is a bonus. You get great tones and sounds that are so rich, that sonically you don't need much. And once you're in that minimalist mindset, you realize you can do so much with so little. And these huge dials are just like one little change, and suddenly there's a new world.”

It’s a kind of sonic fossil hunting, looking for sounds no-one’s heard in decades, and it turns out that Hainbach was actually into fossil hunting as a kid. “I loved it. It’s a thing of like, is there something in that stone? Is that a little trilobite?” The totems gave him a similar thrill. “Just to discover a sound that wasn’t heard by anyone else, not even by the people who made the test equipment, is such a cool thing.”

Of course, I’m abusing this stuff. All the overdrive LEDs on these things are constantly in the red.

Haptic feedback goes a long way, he says, describing the physical effects of working with dials and knobs that are set for ranges way finer than anything musical. “You have to go into the megahertz range, you get such fine control, and a whole new world opened up to me in that micro-frequency range.”

Making the music, he was ‘sweeping through the overtones’ with a filter that has a dial ‘that is as big as my head’ to find new sounds. “Of course, I’m abusing this stuff. All the overdrive LEDs on these things are constantly in the red. Some of these are vacuum tube high-end equipment, so they will break up beautifully. And then sweeping through these broken up sound worlds, there's something where I personally zone away and I find all these details and worlds.”

There’s a steady stream of releases including his beautiful soundtrack to Sergey Stefanovich’s portrait of visual artist Stephen Wiltshire, ‘Billions of Windows’. There was also ‘Isolation Loops’, a soundpack containing ‘pay what you want’ samples and loops of his studio so that people could go into the first lockdown with something to do (“so much potential when everything was cancelled and I needed some kind of valve”). Around 12,000 people downloaded them, and he’s also made collaborative albums through his sub-reddit and Patreon communities. More recently he’s joined up as a mentor with Amplify Berlin on their emerging artists programme. The impulse to share might come from his parents - a teacher and an English professor - or it might just come because he’s mad about the music he makes.

“I think for me, first thing, it’s my own selfish impulses. I just love talking about music, and I love talking about rare stuff and music histories. Another thing is that I don't believe in tricks and I don't believe in the secret weapon. I think everything gets better the more knowledge is shared.”

Sharing has created some neat feedback loops, where viewers on his YouTube channel have inspired new videos or suggested interesting things. He’d already started developing software instruments when someone pointed him to a device from the BBC Radiophonic workshop called the Crystal Palace. The result was his AudioThing Motor. "That’s a very positive feedback loop,” he says. “I get a comment that inspires me to create something that’s both a technique from the 1960s to mix audio but it's also an instrument. And now it exists again in real life. And it also exists as a version in software that people can use. It's rediscovering the past.”

There’s always a risk when a video gets popular some people will try to troll me. I wasn't used to that.

There are of course, two kinds of feedback loops. There're great ones, and there are horrible ones and the horrible ones inspired an art project called Hate Loops.

“There’s always a risk when a video gets popular some people will try to troll me. I wasn't used to that. And I see myself as an artist and I can't close myself to the world because if I closed myself up, I'm just going to make worse art.”

He decided to ‘judo’ his way out of it. “I need to find a way to deflect it. I'm going to collect all the hate that I get. And then I'm going to pull it on the tape loop. And then I'm going to destroy that tape loop slowly over time with knives and sandpaper. And I invited a few other of my YouTube friends that have similar problems, some way more nasty than what I get. They read their hate and I put that recording onto tape and made a whole collage. And then that decayed over seven hours. I had one piano loop going to give a context. And then this collage of two tape loops going. Sometimes the piano loop and those hate comments cut up, they would talk to each. Sometimes it was funny. Sometimes it was sad. Sometimes made me angry. Sometimes it makes me indifferent.”

It was cathartic. “It became like a game of shitty Pokemon. I’d say to Simon The Magpie ‘hey I got a really bad one’. He was like, ‘well, I only get a mad one’. It changed everything and now I'm pretty chill with online hate I because I know I can repeat it again. It was such a healthy thing.”

Finishing up, he shares a favourite corner of his studio. It contains the handmade Ciat-Lonbarde Cocoquantus, Sidrax and Plumbutter modules with which he started his channel, improvising for half an hour or so. “They’re all wooden, so as piano players they feel great,” he says. “The Cocoquantus basically changed my life. It’s not meant to sync anything. There’s no clock or midi. It’s deeply colourful in it’s sound and whenever I throw sounds in there they come back at me in interesting ways.”

It made him realise, he says, that ‘rhythm is something the brain constructs by itself’. It also made him realise that this is one of the few electronic instruments that has the principle of call and response built right in. “When you send a pulse from one thing to another the pulse will send itself back. These things influence each other. You can play together and that’s mind-blowingly beautiful. If I had nothing but this, a microphone and hopefully some kind of piano I’d probably still be happy.”