Words by Emma Warren

The leader of the London Contemporary Orchestra is getting ready to pack her up belongings. “Moving during Covid is different” says the internationally-recognised violinist, composer and electronic music producer Galya Bisengalieva, with typical understatement.

It’s been a busy stretch for Bisengalieva, who was born in Almaty, in Kazakhstan and trained at the Royal Academy of Music and Royal College of Music. She spent most of the isolation provided by lockdown to finish her album Aralkum.

“I finished it in March and April when it was really serious lockdown. Live shows have disappeared for now, It was really good to knuckle down and concentrate on it.”

She’s been busy with ‘a few remote recordings’, film scores and a collaboration with fashion house McQueen – although the the disappearance of live shows has been game-changing. "We definitely have to adapt and find interesting ways,” she says. “We are quite isolated as a species, composers. It’s good we can be with oneself and create but it has had an effect. I’m lucky to have my violin and to be able to put down some drones and create.”

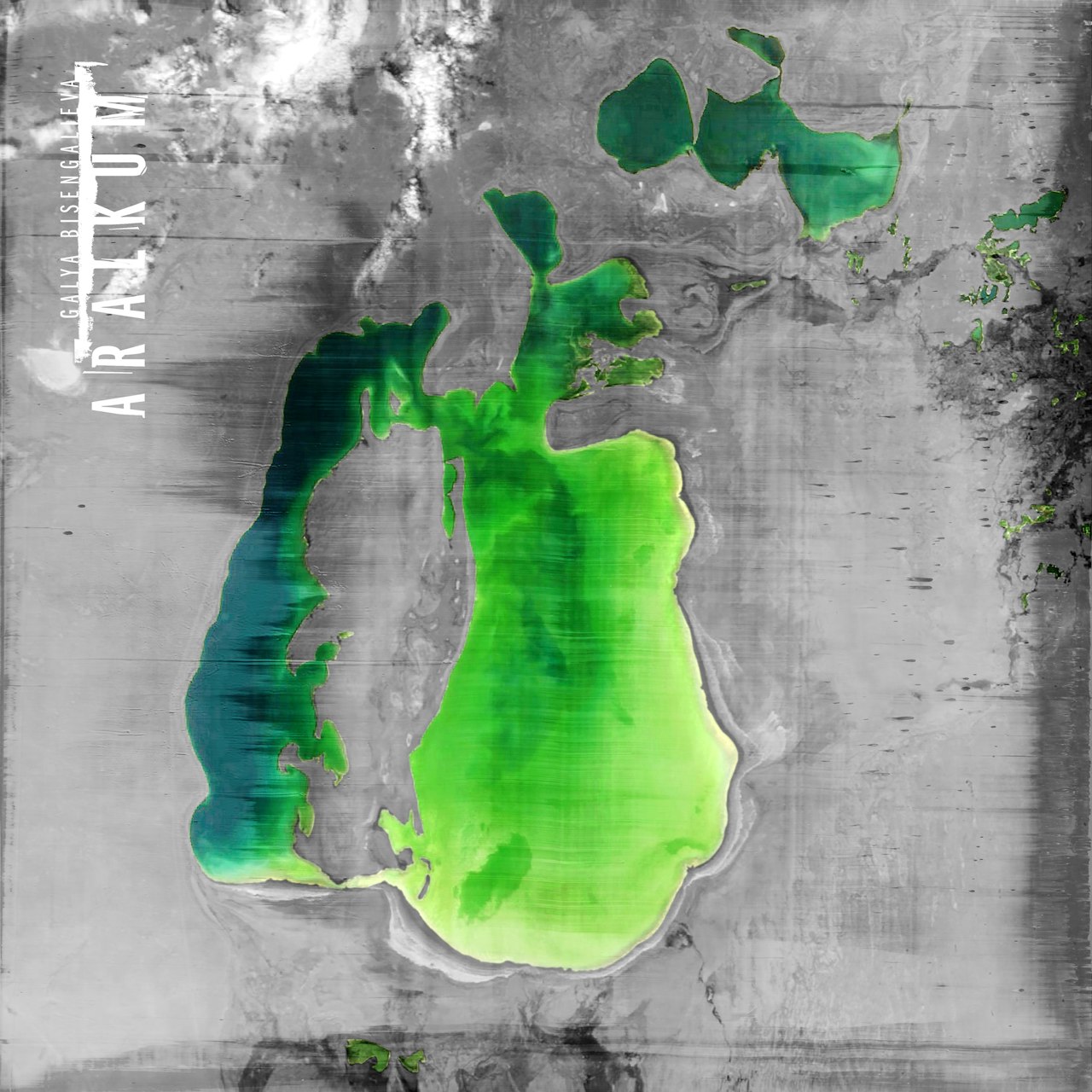

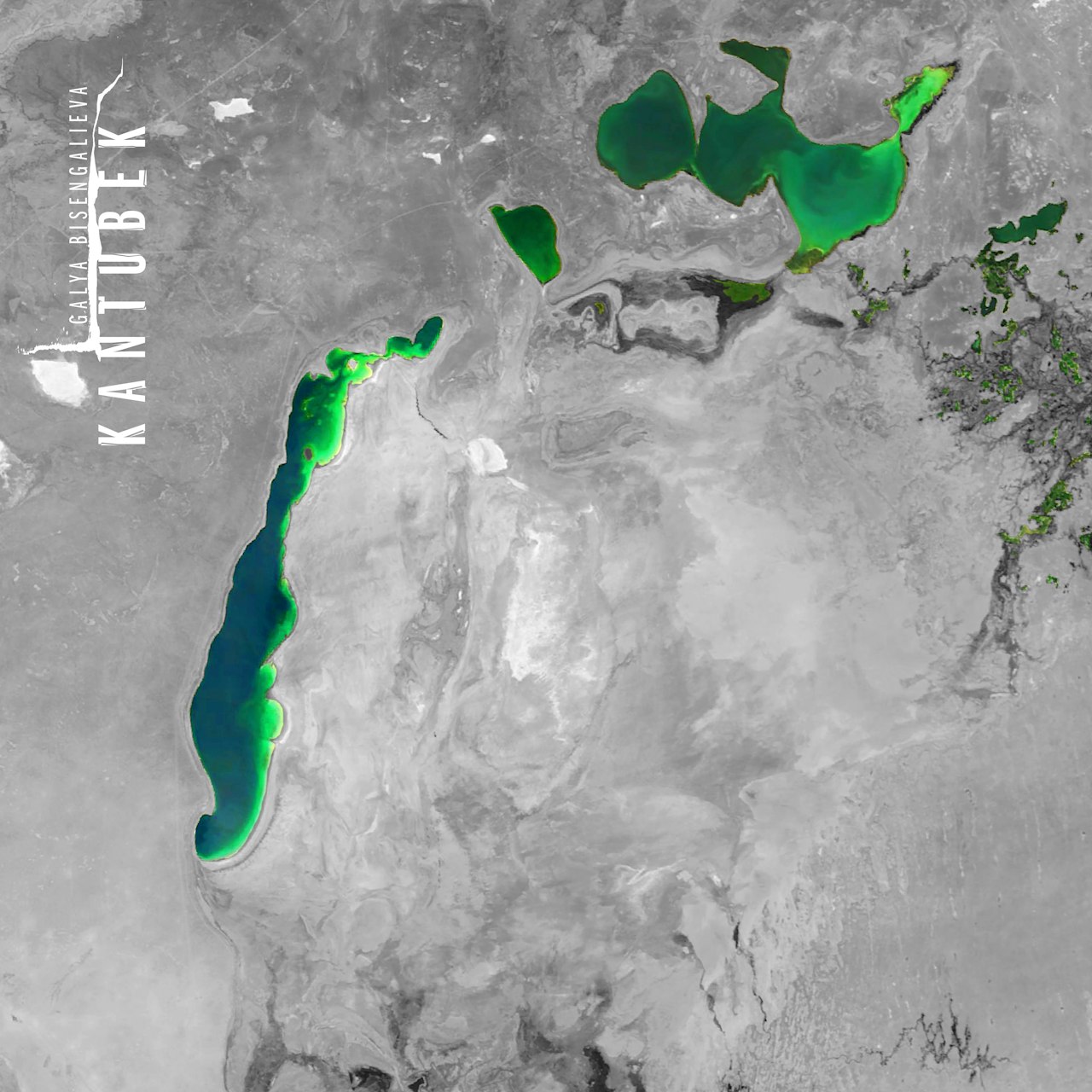

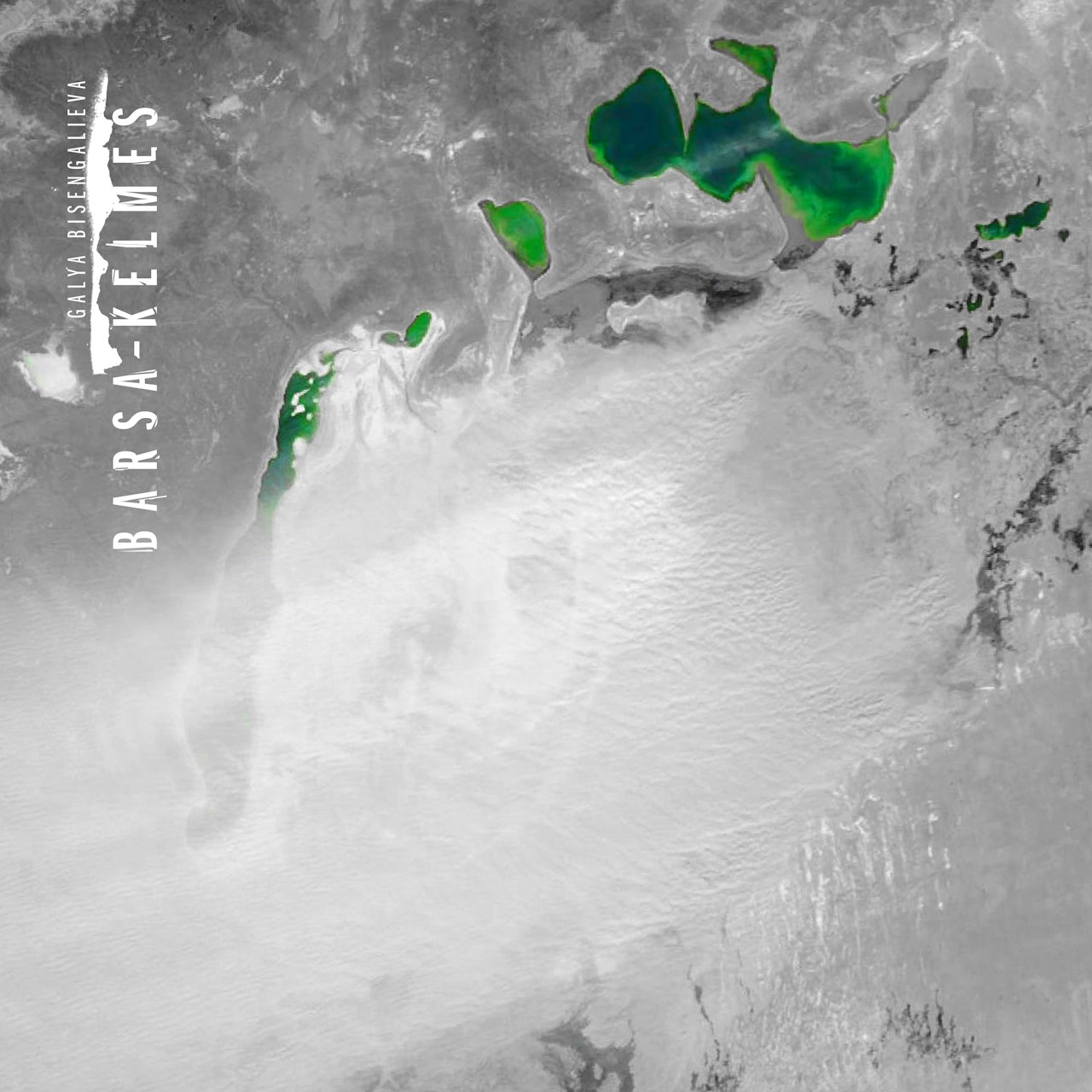

The astonishing recordings on Aralkum use peaked strings and low drones to convey the sorrow and horror of a different kind of isolation – that which happens when your local environment disappears. Some of her mother’s family come from the Kazakh region near the Aral Sea, which went from being the fourth largest lake in the world to a tiny speck, just 10% of it’s prior size, after Soviet irrigation projects in the 1960s diverted the rivers that fed into it.

It’s an environmental disaster but it’s also a cultural disaster, not least for the people who live nearby. “I grew up with the story of the shrinking of the Aral Sea. Everybody knows about it in Kazakhstan, but it’s not as well known in the West,” she says. “The writing of Aralkum came out of an innate need to tell the story of the tragedy and how it’s been overlooked and ignored.”

I was playing the solo violin or improvising on scores, but I wanted to be heard in my own right.

It’s a record in three parts: Pre-Disaster, Calamity and Future and it comes with two contrasting visualisations of the music and the story. There’s unending aerial drone footage of what looks like arid land but you realise is dry seabed and a surreal black and white animation directed by Kazakh photographer Damir Otegen and animated by fellow countryman Temirlan Uali.

It was important for her to collaborate with people who knew the region firsthand and had a real connection to it, although the end results are also a reflection of COVID-19. “It came from not being able to travel to Kazakhstan. Originally we were going to shoot at the Aral Sea but then the lockdown happened so we thought how can we do this at a distance? That’s how the animated aspect came in. I’m glad it happened this way because I think it’s quite powerful in portraying the disaster."

Bisengalieva works a lot with drone and multi-layered strings – Umay from 2019’s EP TWO had 60 layers of violin drone – and these processes find a powerful expression in Aralkum. She began pushing the edges of her sound after acquiring a Whammy guitar pedal. “That gave me an opportunity to tune the instrument to treat it like a cello, a double bass. It really opened up a lot of things for me,” she says. “It was a starter to my compositional world.”

“I manipulate the violin. I improvise. I work a lot in Logic, with found sounds. I played around with field recordings from the area, like wind hitting against the rusted hulls of abandoned ships. I researched the wildlife that used to be there and found the sound of the birds. It’s connected to nature, to sounds that are present in the area right now. It’s not just my composition.”

It was recorded and created simply, just the composer at her computer and a few handmade, Russian-built Soyuz microphones. “I think the sound of the violin is quite particular and you have to capture it in the right way. You can make the violin sound bad quite easily,” she says.

We’re used to hearing the instrument with this beautiful sound, evoking pretty melodies and I want to break that up a little bit and see how far we can push it.

In 2018 Bisengalieva released the 300-run limited edition EP ONE on her own NOMAD label containing music from herself, Organ Reframed founder Claire M Singer and French pianist Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch . EP TWO , released the following year another of her compositions along with music by Manchester-based electro-acoustic artist Chaines and British-Iranaian turntablist and composer Shiva Feshareki.

She’d already been working outside the classical realm of her training – she has credits on Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool and Frank Ocean’s Blond alongside collaborations with Moor Mother, Pauline Oliveras, Steve Reich and Hildur Guðnadóttir – but the releases gained her new attention from The Wire to The Quietus and The Guardian.

The EP collaborations, she says, were designed to push the boundaries of the instrument. “I’ve come from a traditional, classically-trained school. I’ve done chamber music and concertos in the classical genre. I wanted to move away and see how it could be pushed into a more electronic, ambient and drone world.”

Drones are key. “I think it’s the simplicity, the minimalist emphasis it gives, of sustained sound and what kind of emotions that can evoke. It’s simple on the surface, it’s not a lot of notes, mostly, but the deeper you go into it and the more you listen, you can get a lot of depth out of it.”

Sustained sounds can also challenge you, she says. “Maybe they can give you emotions you don’t particularly envisage having. It’s that aspect that fascinates me. It can be a difficult process, listening. It does require attention and patience.”

I hope people if they’re listening, can get to know a little more about this story. To hope for the future and maybe inspire a moment of reflection of how we can take care of our surroundings.

Her own music aside, she’s in demand as a contributor to film soundtracks. Mostly, she added improvised strings or solo violin to productions including last year’s Honey Boy by Alex Somers, the Daniel Day-Lewis historical drama Phantom Thread and Lynne Ramsey’s award-winning You Were Never Really Here.

It was contributing to film soundtracks that made her quietly determined to create her own compositions, beginning with the EPs and her own label and culminating in the stunning music on Aralkum. “It came out of … frustration,” she says carefully, before returning to the pressing task of packing up boxes. “I was playing solo violin or improvising on scores, but I wanted to be heard in my own right, I guess.”