Words by Anton Spice

The first thing that hits you is sound. A growling, guttural voice, unsettling in the extreme. “Power over spice, power over all.” You feel the vibration in your chest, pressing you back into your seat. Sound is a sensation that can defy rational explanation and if there’s something Hans Zimmer enjoys it is making you feel without knowing why. “The thing I love about music [is that] you can move people within a second.” How he does it is another question entirely.

Like Part One, the sonic world of Dune: Part Two is all-encompassing. And like Part One, the musicians and collaborators Hans Zimmer has surrounded himself with spending most of their time just trying to keep up. One of those is synth maker Urs Heckmann. “Urs was asking, why do I really need five resonators?” Zimmer beams. “I need five resonators because I have this vision of how things are supposed to sound!” When he’s not haranguing his synth man, Zimmer is sending his virtuoso woodwind player Pedro Eustache to the hardware store to buy lengths of PVC piping or demanding something ungodly from a heap of stolen sheet metal. “Do you bow it? Do you hit it? What do you do with it??” Zimmer’s smile gets even wider. “I was driving people crazy!”

I need five resonators because I have this vision of how things are supposed to sound!

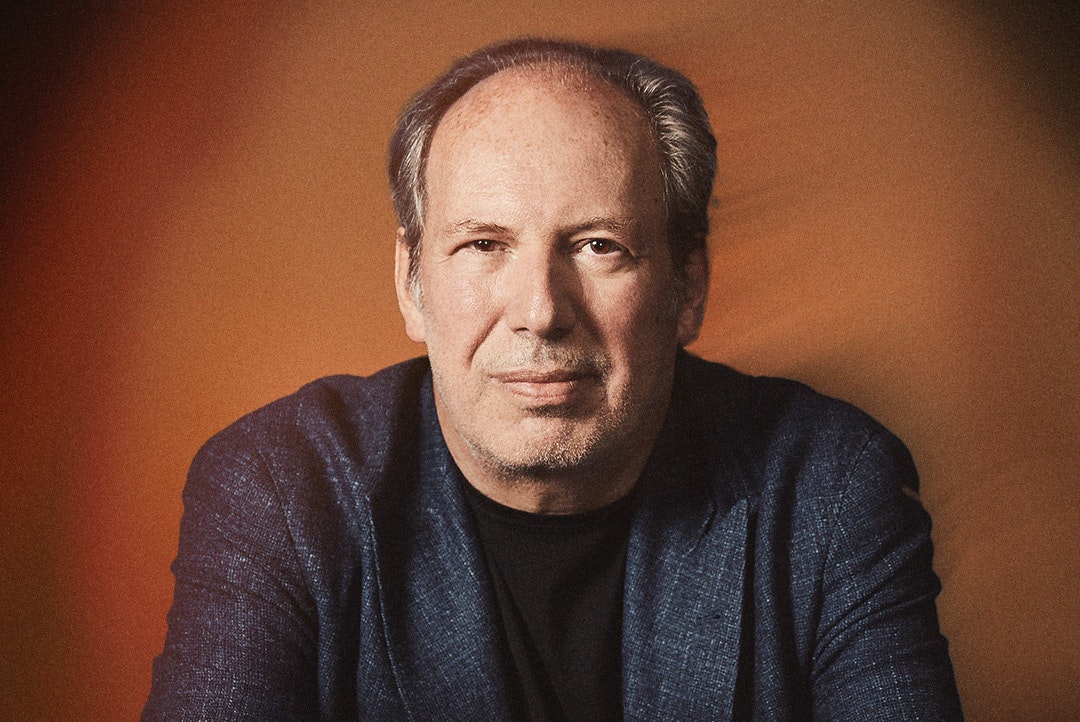

If there’s a maniacal energy to how Hans Zimmer discusses his work on Dune that’s because he has been waiting his whole life to do it. At the London premiere of Dune: Part Two in February, the 66-year-old composer was asked how he felt when he was first approached to work on the project. “Like a crazed puppy,” Zimmer responds, breathless with excitement. When I meet him the following day, the high has worn off a little and he is neck-deep in interviews, wearing a Trachten jacket and holding court in a large room of a five-star hotel. It’s a marathon junket and I wonder whether the schedule has taken its toll. At one point he says that orchestras are fundamental to what makes us human because, apart from anything else, “I haven't heard a lot of dogs writing orchestral music.” This crazed puppy notwithstanding.

And yet the sound of Dune is not that of the orchestra. Instead, Zimmer relies more on electronic synthesis, modified instruments and speculative sonic experiments than he does on classical convention. From Gladiator and Inception to Batman and Pirates of the Caribbean, the films he scores demand bold, sweeping visions and a degree of bravura to carry them. Visions where only five resonators and 21-foot PVC tubes will do. On Dune, Zimmer is like a dog that got his bone. “After all,” he says, smiling again, “the operative word in music is play.”

Based on the 1965 sci-fi novel by Frank Herbert, Dune is a story of interplanetary conflict fought over control of “spice”, a psychotropic resource that is only produced on the desert planet of Arrakis. Unravelling around themes of power, love, environmentalism and colonial extraction, Dune’s reputation has preceded it as one of the most complex and challenging sci-fi narratives to adapt for film. The only movie to emerge from the three years Alejandro Jodorowsky spent failing to make it was a documentary about Alejandro Jodorowsky failing to make it. Such was the reaction to David Lynch’s 1984 attempt (soundtracked by Toto no less) that it almost ended his career before it had really begun.

Fast forward four decades. Zimmer and director Denis Villeneuve bonded over having adored Herbert’s original text as teenagers and in Zimmer’s words “constantly regressed to where we were when we read the book”. This boyish enthusiasm makes light work of Dune’s cultural baggage. “He [Villeneuve] makes it safe for us to go onto very dangerous ground,” Zimmer purrs. How else could you begin to score a scene that took three months to film, in which your main character is riding a giant sandworm the size of a freight train across the open desert?

The thing I love about music is that you can move people within a second.

Set largely on Arrakis, Dune: Part Two follows the journey of Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) as he becomes accepted by the planet’s Fremen people, helping them take on the dark Harkonnen forces, grappling with his destiny and falling in love with Chani (Zendaya) in the process. There is of course much more to it than this, but if Jodorowsky couldn’t realise it in three years, you’ll forgive me for not trying in three lines.

Perhaps even more than 2021’s Dune: Part One, this second instalment feels like it is being driven by sound. A continuation rather than a sequel, many of the film’s sonic elements – the resonance of the thumper, the fluttering mechanism of the ornithopter, the spectral melody of the wind – were already established. Villeneuve has said that editor Joe Walker used the “structure of the sound” to create a “map” on which the images were based. That Zimmer had already written some of the music before they started shooting is also suggestive of a score that takes the narrative by the hand.

What Zimmer and his collaborators create then are perhaps best understood not as songs that reflect the story and more like atmospheres in which the story unfolds. The desert – dry and vast – has an internal sonic logic governed by more organic instrumentation, the pseudo-Fascist realm of the Harkonnen one which is techno-monstrous. When these worlds blur, industrial electronics bite into the natural fabric. Melody is used sparingly throughout, amplifying moments of human connection and beauty in an otherwise hostile and disorientating world. The presence of the human voice, Zimmer has said, is the only constant he could project with confidence into the future that Dune inhabits.

This desire to capture the rich internal lives of the characters, the environments they inhabit and the urgency of the action makes the soundtrack and sound design almost indistinguishable. That Zimmer has worked for several years with sound supervisor Richard King made this all the more intuitive. When the monstrous spice harvester comes under attack, the accompaniment is physical in the extreme. “It's pretty mean, isn’t it?” Zimmer smiles. Crunching drums head in one direction, sawing metal in another, the breath of the characters in a third. The whole thing feels less like a piece of music than a chunk of rock, hewn from the thumping depths of the earth. Rather than progressing in a linear sense, the composition is so densely layered that it feels almost lateral. Zimmer’s eyes light up at the word. “It’s not horizontally written,” he elaborates. “You can play it backwards and you can play it forwards and you can play it upside down.” Each movement on this score is three-dimensional and as solid as a sandworm.

“Ever since I was a kid, I wouldn’t just hear a tune, but I would hear the full...” He breaks off, preferring a visual metaphor. “I would see all the staves. I always saw the vertical in my head.” Rather than focus on the notes, each instrument - whether woodwind, horns, percussion or strings - became what he calls “sonic elements”, as material as bits of old PVC tube to cut up and play with. Another instrument unique to this film is the Osmose, a French-made synth sensitive to the movement of a player’s fingers on its keys that “only” took ten years to build. “It finally allows you to be as expressive as a violin,” Zimmer enthuses, before heading off in a different direction altogether. “But if you think about a violin, what is it? It's a piece of wood with some dead cat attached to it, and you scrape some horsehair across it.”

The only thing I can go by is my instincts, putting some sort of framework in place and then trying to be good enough to actually play it.

This capacity to think laterally about music and deconstruct its instruments is rooted in Hans Zimmer’s childhood. His mother was a classically trained pianist with a good ear, and his father was an “extraordinarily appalling” jazz clarinet player and inventor who enjoyed taking things apart. Aged 6, young Hans was given piano lessons but lasted no more than two weeks, bored stiff by the chords and charts of traditional music tuition. Growing up between Germany and the UK in the 1970s, it’s not surprising that he gravitated towards synthesis instead.

Zimmer’s career thus began as a musician. He played keys and synths in Krakatoa, shared a house with Giorgio Moroder without knowing it and can be seen bobbing away in black leather behind a keyboard on The Buggles’ Trevor Horn-produced ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’. It wasn’t until he began scoring soundtracks for indie films in the 1980s however that Zimmer began to find his niche. His break came in 1988 when he was asked to soundtrack Barry Levinson’s Rain Man. Combining steel drums and the CMI Fairlight synthesiser, the soundtrack set the tone for a career spent combining acoustic instrumentation and electronic synthesis. Rain Man was subsequently nominated for best original score and in the 35 years that followed, Zimmer has soundtracked over 150 films, winning two Oscars along the way, for 1994’s The Lion King and more importantly, Dune: Part One. Now in 2024, Zimmer’s name is practically synonymous with a certain kind of Hollywood bombast that, in his own words, treads the line between emotion and sentiment. For the last few years, he has toured the world playing classics from his repertoire under the title The World of Hans Zimmer. He’s not wrong. You could say that Hans Zimmer exists in an orbit of his own.

Even on planet Zimmer, a degree of gravity still applies. “Here's the dilemma of the composer,” he explains. “The dilemma of the composer is that you write a piece of music that you think is appropriate, but if it doesn't move, or touch, or is right for the scene that the director envisions, you can't turn around and explain to him why he should like it.” A note, he says, can move you in a second. Or it cannot. “Music is indefensible.”

So indefensible in fact that Zimmer says he still gets nervous when he shares his work for the first time. “It's a scary thing because I'm playing something I worked very hard at, being as honest and as open and as fragile as I possibly could be, and if they don’t like it, if it doesn't land, it just destroys you.” In that sense, his reputation as a maverick works both ways. He may be “a pretty good synthesist” but is the first to admit that he became a composer “by accident”, qualifying his successes with the kind of modesty that only makes them shine brighter. “I'm definitely the most uneducated composer who is working, so the only thing I can go by is my instincts, putting some sort of intellectual framework into place and then trying to be good enough to actually play it.” What frustrated him most about those early piano lessons was that his teacher couldn’t explain to him how to get the ideas out of his head and into his fingers. Even now, articulating what’s going on up there remains the biggest challenge. “And it gets worse, because the more I write, and I've written quite a lot…” He turns to me. “You know this! You start with the blank page, and doesn’t the blank page over the years get whiter and whiter and just singe your eyeballs? You sit there and you go, 'what am I going to do?'”

I let him answer his own question. “I always start with nothing. It has to be nothing. I might not know the notes yet, but as I build the sound, the notes come, or the notes are suggested by the sound, or the notes are suggested by the content of the scene.” In that sense, Zimmer describes himself as a film composer rather than a composer per se, and it’s striking how many times during our conversation he returns to visual metaphors to explain his process.

On Dune, the notes suggested by the environment lean into the sonic textures of the desert. Sand and wood feature heavily, as does a sensitivity to wind and open space. As far as synths are concerned, Zimmer calls the pre-set “the enemy of the imagination” because it blunts the possibility of a new sound with one that already exists. “It [the desert] doesn’t sound anything like this, but that's sort of not the point,” he explains. “I'm allowed to use an abstract, painterly approach to things.”

The palette he draws on could generously be described as pan-global, and he says he is careful not to borrow tropes from North African musical traditions or impose North European classical arrangements on a landscape and visual aesthetic that owes much to the Middle East. In Part One, Zimmer asked his cellist to play her instrument like “a Tibetan War Horn”. The duduk, an Armenian reed woodwind instrument made of apricot wood is present again (you’d recognise it from Gladiator too), as is the banshee-like cry of vocalist Loire Cotler, which cuts across the desert with chilling force. “There are probably more flamenco chords in some of the stuff than people realise,” Zimmer continues. “If you think about flamenco, you think about Romani music and you think about how it comes from the north of India down to the south of Spain, and it's tribal, and I thought there is something about that I can make the film relate to.” Events on Arrakis may serve as a powerful allegory for environmental destruction, resource extraction and colonialism, but it is still a planet of its own, flung into the distant future. Like a landscape with layers of history, each sound comes with its own set of references and associations, some real, some imagined.

It's this crazy thing that music can only exist by disappearing. As soon as the note is played, it only remains as a feeling inside you.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the very first piece of music that Zimmer wrote for Dune: Part Two, long before shooting had even begun. Every night on The World of Hans Zimmer tour, his orchestra would play the piece that would become Paul and Chani’s love theme without telling the audience what it was with the hope that if they came to see the film, they’d recognise it without knowing why. “It’s so sparse,” Zimmer explains, that after so much time spent immersed in a harsh story about revenge unfolding in an inhospitable environment, the purity of the melody is “almost shocking.” Never mind love, Zimmer’s composition is “more about loneliness and more about alienation and more about space and time” than anything else. That these can be the defining themes of an unrepentantly complex sci-fi epic speaks to the kind of film Dune really is.

In truth, for all the booming sound design and sweeping crescendos of the score, the most powerful moments in the film are those where the sound dissolves completely. These moments of silence are held in anticipation of sound to come. In Zimmer’s hands, they take on a weightless quality, like that guttural moment at the top of a rollercoaster where your stomach heads north before the plunge and the whole world feels like it is about to end. “Deafening” is the word he uses. Silence on Arrakis is created by a process of subtraction, often leaving nothing behind but a residual vibration, the hum of the Earth that we perceive to be emptiness. Zimmer returns to the instruction he gave his musicians at the start of the process, and the true purpose of all those damn PVC tubes. “Can you make the sound of the wind whistling through the sand dunes?"

Conversation with Hans Zimmer switches between registers and frequencies with ease. He will tell you about the specific material qualities of the violin before pontificating about the role of orchestras in what makes us human. He will revel in the minutiae of music making and indulge grand statements about its philosophical intent. Occasionally he’ll talk about dogs writing symphonies or make a joke at his own expense, but mostly he’s deadly serious about the craft of composition, his responsibility to the film, and the effect it has on the audience. “It's this crazy thing that music can only exist by disappearing,” he ruminates, as our interview draws to a close. “As soon as the note is played, it only remains as a feeling inside you.”

Leaving the cinema after watching Dune: Part Two, it was the sound which lingered most. Walking down New Oxford Street at rush hour on a dreary Tuesday afternoon, more than anything I was struck by how quiet, soft and parochial London suddenly seemed. “After we bombarded you for 166 minutes, didn’t you feel in a funny way just for a moment that your normal world was the alien world?” Zimmer asks when I mention this sensation to him a few days later. “Didn’t you feel that your experience had shifted and you were feeling things in a different way sonically?” I nod. Hans Zimmer’s mischievous smile returns. “That was the idea.”