Words by Joe Williams

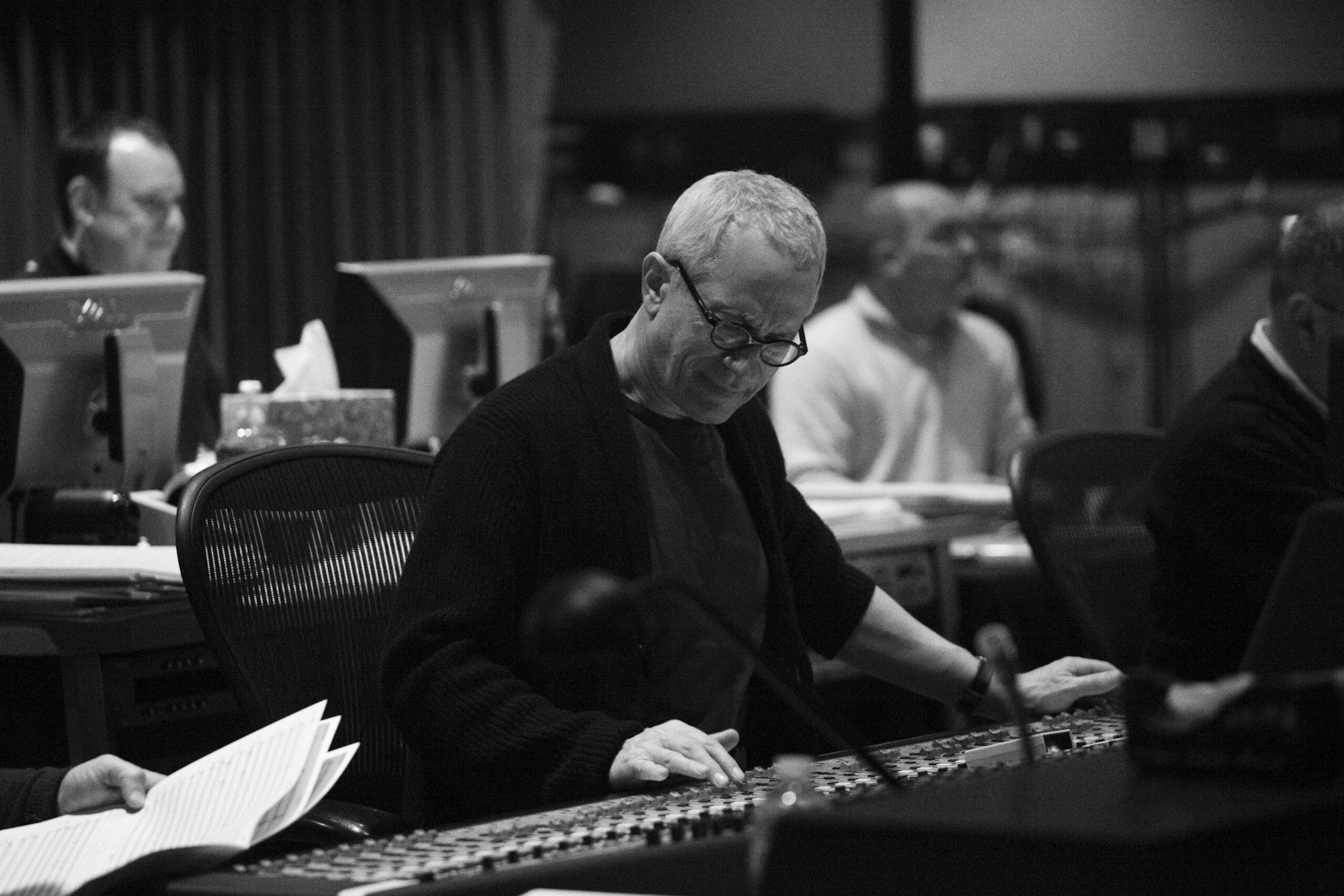

With over 100 films under his belt and more incoming, James Newton Howard is showing no signs of slowing down.

His illustrious career has seen him nominated nine times at the Oscars, breathe new life into King Kong for Peter Jackson, work with Hans Zimmer to revive Batman for the 21st century, and craft the signature soundscape of the multi-million blockbuster franchise, The Hunger Games.

The prequel for this series, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, is playing in theatres right now, marking his seventh project with acclaimed director Francis Lawrence. Of all the filmmakers Newton Howard has worked with, however, including Michael Mann, Terrence Malick and even Barbara Streisand, he is most closely associated with mystery auteur and modern master of suspense, M. Night Shyamalan.

Despite such a varied career, which spans four decades and every genre under the sun, one element of Newton Howard’s artistry remains the same — a strong passion for the orchestral, and a desire to preserve classic sounds in mainstream modern cinema.

When returning to long-standing franchises, like with the Fantastic Beasts series or the upcoming Hunger Games prequel, do you feel like you’re building upon an existing world or starting again with each title?

I think that the hardest thing is to get to know the previous score. Once you’ve finished a movie, the themes and motifs and every nuance of that score are still alive, but you step away from it for five or six years and a lot of those things just disappear. I like to rearm myself with a new toolkit to start on the next movie. It was slightly different with the Hunger Games because there'd been quite a long period since the last one. It had been eight years, and also this was a prequel, so I had to be very careful. The idea was originally to use as much Hunger Games material as possible, but I found that once I started working with this movie, which is an entirely new beast from the last one, it needed a whole new concept, new ideas and a new feeling. One of the mandates was, “Let's try not to have any electronics in it”, which I thought was interesting because it made me focus purely on orchestration — which I enjoy. But it had a whole different kind of tone. Of course, I did recall some of the main themes occasionally, in different moments, but mostly, it was just all new material that seemed to fit this new iteration of the story.

I like to rearm myself with a new toolkit to start on the next movie.

This ethos of limiting electronics on the score — was that an early conversation you and director Francis Lawrence had?

Yeah, it was, and I understand the motivation. This story is set something like 65 years earlier, so a largely electronic score wouldn’t feel right — the world of Panem is not quite as modernised as it is in the rest of the franchise. And that really freed me, because I immediately knew, “I can't do this, I can't do that, but I can do this.” Omitting electronics enabled me to make decisions that I hadn’t often made before. There are a ton of woodwinds in this score; a lot of these low, weird, Bernard Herrmann- kind of scary sounds that are great. I loved doing that. It's a lot more orchestral than the other four movies.

The film industry has undergone significant changes in recent years. How has the evolving landscape influenced your approach to scoring, and do you find yourself adapting to new cinematic trends in your compositions?

I like to think that I don't just pursue evolving cinematic standards in terms of what is making movies more popular now, or what is attracting more of an audience. I think part of the deal is that I still adhere to the idea that melody is super important. I know a lot of directors don't particularly like melody; they think it feels too emotional. That's okay, I do think emotion can be also indicated with electronics, and I've heard lots of good electronic scores that are quite moving in places — but where I'm most at home is doing big orchestral scores. Big fantasy adventures, romances, you know —- epic things. And, to be honest, the whole aesthetic of that stuff hasn't changed in my opinion. When I do a movie like The Hunger Games or Fantastic Beasts, it's broadly orchestral, and I don't think that will change.

What allows composers to succeed is to be malleable.

There has always been a place for scores like that, largely thanks to John Williams, who reinvigorated the whole idea with Star Wars. Hopefully, that will persevere. I'll tell you one thing that has changed for sure; the amount of turnaround because of Avid. Back in the old days, there was no way they were going to restructure the whole movie every day because it was too laborious to have to cut things on the table. But now, I’m sometimes given a new ending twice a day. Everybody's experimenting with it, and then they test the cut and they don't like it, so they go back to another version. So I think, in a post-production context, things have seriously changed. What allows composers to succeed is to be malleable.

How has the digital age influenced your creative process? Do you incorporate digital elements into the way you work in a way that differs from earlier in your career?

I think the transition was fairly seamless, because I was in Elton John's band in the 1970s. Elton was very generous, allowing me to do the electronics and then do orchestral overdubs to them. I could add synthesisers, and I could add orchestras, so I learned to be very comfortable experimenting with both. From that moment on, when I started to do movies, I would always combine orchestral scores with electronics — if I had the budget. With The Package (1989), which is one of my first big action movies that I did with director Andy Davis, I was using lots of electronics. It wasn't that easy at the start, because I was working on the MPC 60, which was prone to crashing, and the Linn 9000.

The evolution of the sequencer, for me, has made my job a whole lot easier and changed the way I write.

Then somebody introduced me to a sequencer called Studio Vision. So I worked on that, and I loved it, and then along came Cubase. And now I'm a Cubase guy. All of these things massively facilitated the demo-making but I guess to some extent, sounds in general can be inspiring. A lot of times my assistant will bring me a whole new palette of stuff that he's investigated, including some of Spitfire Audio’s stuff as well, and we also make our libraries — but one simple sound can sort of be a main theme in a way, you know, just repeating one kind of sample. The evolution of the sequencer, for me, has made my job a whole lot easier and changed the way I write. I used to write a lot more on paper. But when you write an idea out, literally pen on paper, you just can’t see its relationship to all the other parts. So… something gained, something lost, I would say.

You’ve been working as a film composer for nearly 40 years. How has the way you sit down and approach each new project evolved?

I think the biggest change in my career is no longer starting right off to the picture. When I was working with M. Night Shyamalan at the very beginning of our collaboration, Night would always like it if I wrote some stuff before he shot and just sent him little demos. I did that — then I started writing entire suites. Just ideas with no picture, like seven or eight minutes long. He'd hear those and he'd pick out moments: “Oh, I really liked this part. I like that sound.” I’d go back and investigate that one idea further. I did that a lot with Hans [Zimmer] too. And for the Batman movies [Batman Begins, The Dark Knight].

I became very interested in having the freedom to investigate ideas without worrying about the image.

It was Hans that encouraged me to do more of that. It was a great idea because then you're not constricted by whatever the cut is. It’s not like you’re writing a beautiful or exciting piece of music, and then all of a sudden a car crashes through and that piece of music has to disappear. I became very interested in having the freedom to investigate ideas without worrying about the image. I think it's very liberating. Inevitably, I would go back and look at the music once I had the ‘finished’ film. I would go back and take certain sections I’d worked on, and I would wonder if it was going to work in this scene. Without fail, a good portion of all of those suites ended up in every movie that I ever did. I think what young composers get hung up on sometimes is just trying to write too early to the movie.

What would you suggest they do?

Just write some music; write some music without picture. It’s really healthy because if you don't, you're only scoring someone going from the door, walking out to the car — they start kissing, and suddenly you’re interrupted, you feel like you have to change the music. Nothing is going to tell the story if you do that. Plus, if you do the longer suites and longer arcs, and not think of it in such small bits, there’s the possibility of revealing to a director things in the movie that they didn't see. There are always surprises for me, too. Happy accidents happen all the time. A lot of times directors have taken some of my music from other movies and used it as temp score for another project, and they’ve put it in places I never would have thought — and I often thought that it worked better than it did in the original. I would never have gone to that place. It’s funny because temp music doesn't bother me at all. I actually think it's very informative.

The more I listened, the better composer I became.

What would you tell your younger self if you were to start a career in music or film composition?

Make sure you invest as much as you can on your gear, however basic or fundamental it is! Write every chance you get. Don't turn anything down — I certainly didn't. I had maybe small regrets about that later on with some crappy movies at the start, but I always developed a skill set while I was doing it. None of them were a waste of time. Most importantly, though… I could have been a better listener. When I started doing film, I was somewhat arrogant. You know, I was a pretty good pianist, I was a pretty decent synthesist, I played with Elton John, etc. And so I had this attitude that I was going to tell the director what the story was really about. And, consequently, I would get into some unpleasant conversations with the filmmaker, until I realised I needed to stop talking so much. The more I listened, the better composer I became — but it took me 10 years to learn how to listen.

Can you reflect on the dynamics of your artistic partnerships, particularly with long-standing collaborators?

These days, there’s definitely a degree of shorthand and, more importantly, confidence and trust. A director will say, “Wow, you did it really well last time, so I'm going to presume you're going to do it really well this time.” My process is always the same, just with slightly different colours. It's all about communication and connection. I don't always believe in the necessity of spotting, necessarily. What I prefer is for them to give me the movie, and go away for three weeks, and then come back and I'll play them the things that I think are working — and they tell me what they think.

My process is always the same, just with slightly different colours. It's all about communication and connection.

With David Yates, it’s a long curve. He’s a great director, and I love him to death, but on his movies, it’s like a seven-month kind of thing. He’s a note-giving machine. We would have some playbacks with what I've been working on for a long time, and he’d say, “Ah, that's a good start.” What do you mean, a good start? Then you take somebody like Francis [Lawrence], who I'll play a big, orchestral, complicated cue — and he'll be like, “Awesome.” And I'll ask, “But Francis, what about this bit?” He’ll just go “It’s great.”

Of all your collaborations, your biggest is probably with M. Night Shyamalan. How has that relationship developed?

I feel like his older brother, and I’m sure he feels like that too. I mean, we are brothers. When we first met, we had a very short meeting in LA before The Sixth Sense. And he hired me to do it, and we wrote the score in about six weeks. Afterwards he said, “You know, you didn't get nominated for an Academy Award.” And I said, “Oh, yeah, I know.” But he did — or the movie did; it got six. He said, “Well, the reason you didn't get nominated was because there was nothing singular about that score.” It was a great score, and it really worked for the movie, but it was not singular in the sense that people would hear a few notes and know what movie that was, like Jaws. Me and Night went through triumphant times and precarious times together.

I’m compelled to help directors in every way I can.

Is there something specific you look for in a potential collaborator?

Generally, I think I have to be close with a director to do well. In order to succeed as a film composer, you have to feel sorry for the director. And I really believe that, because they have such a terribly difficult job. By the time they come to you, the composer, they’ve spent all the money. Maybe the actors weren't as good as they were hoping. Perhaps the movie isn't working as well. So they're coming with their hands out, saying “Help me!” I’m just compelled to help them in every way I can.

How does it compare to working with first-time directors? The most notable example that comes to mind is your score for Dan Gilroy’s Nightcrawler.

With Dan, it was new territory, but he knew exactly what he wanted. Dan actually gave me the best possible note, the one single note he gave which really made that score pop. I was writing some of the tension sequences, when he's moving the body around and stuff, as traditional thriller music — kind of scary. Dan said, “James, I think you're thinking about it in the wrong way.” He said, “When he's doing these abhorrent things, I want you to pretend like he's your son, and you’re proud of him. This is a celebration of him.”

Creating an interesting dissonance was the secret to my success on Nightcrawler.

I went back and wrote this kind of positive, anthemic music, and it created such an interesting dissonance in the movie between what was apparently on screen and what you were hearing. I think that was the secret to my success on that movie. That was probably the best note a director ever gave me.

How has collaborating with new talents influenced your musical style, and what unique elements do emerging composers bring to the creative process?

My assistants are great composers and programmers in their own right. They learn a lot here, that's for sure. And I push them out of the nest every about five or six years, and every one of them that's ever worked with me is working. I've learned a lot from them, too, because they have critical ears and then I can ask them what they honestly think about the work. So there's a back and forth with young composers that I like very much, and I really enjoy helping them get jobs. Young composers, they can show me better ways of doing things technically, too, because they're just much smarter than I am in that regard. I was never like that when I was 26. I was a complete basket case. So these kids are just so talented, and so lovely to be around, and their energy and their optimism really helps me.

You touched upon the simple importance of melody, and how some directors steer away from it. What other elements, to you, are fundamental to creating a great score?

You need to make sure that you're telling a story and not just making noise underneath it. I think a great film score interacts perfectly with the other two players, being dialog and special effects. I mean, it's really a triumvirate that has to play nicely together. I think an identifiable motif or theme can be very useful in terms of describing a character. You have to be careful about whose emotional point of view we are in, which is something Night really helped me with. He'd say, “Oh, no, that's his point of view.” So, above all else, have clarity about which character you're with.

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes is playing in cinemas now.