Words by Amon Warmann

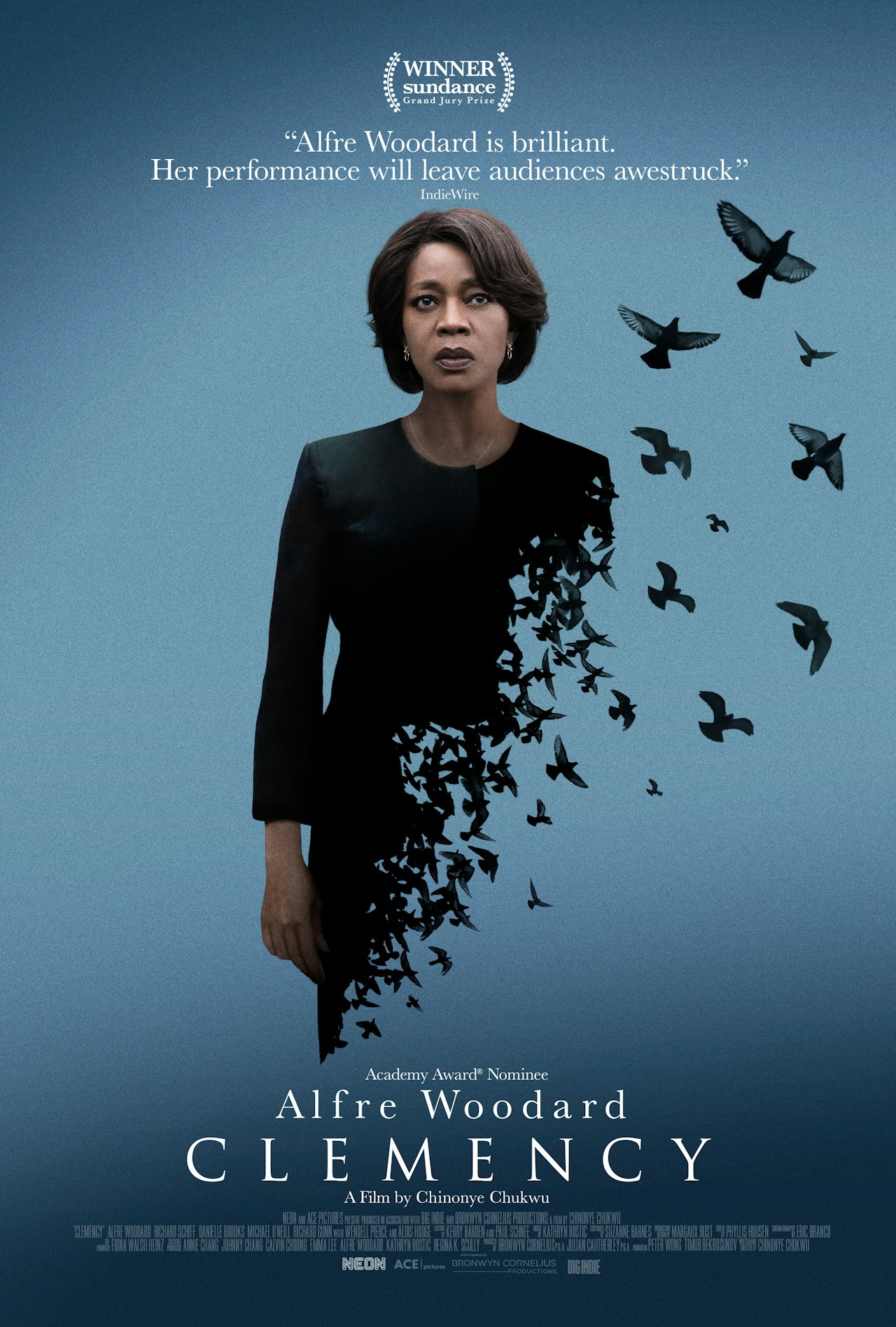

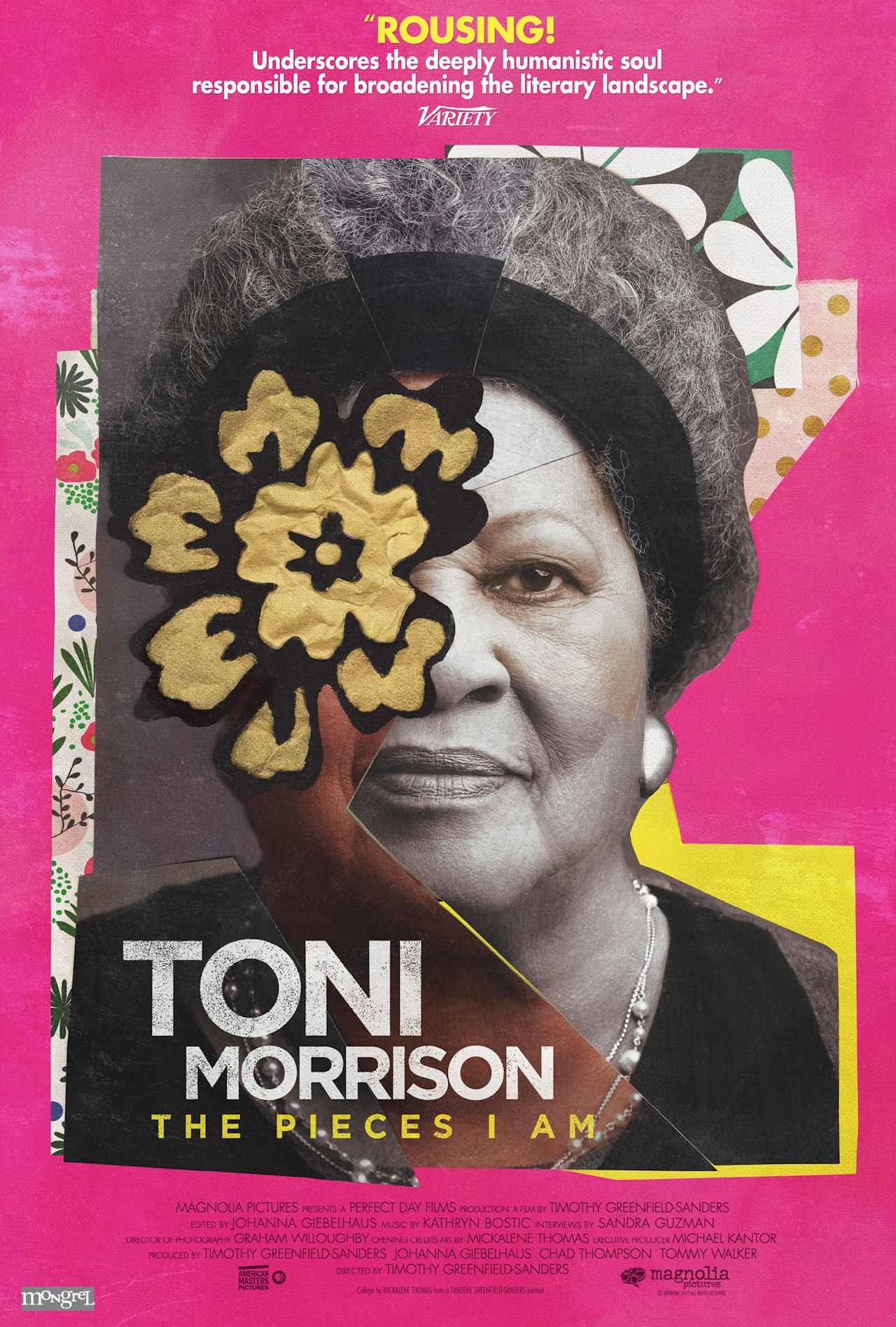

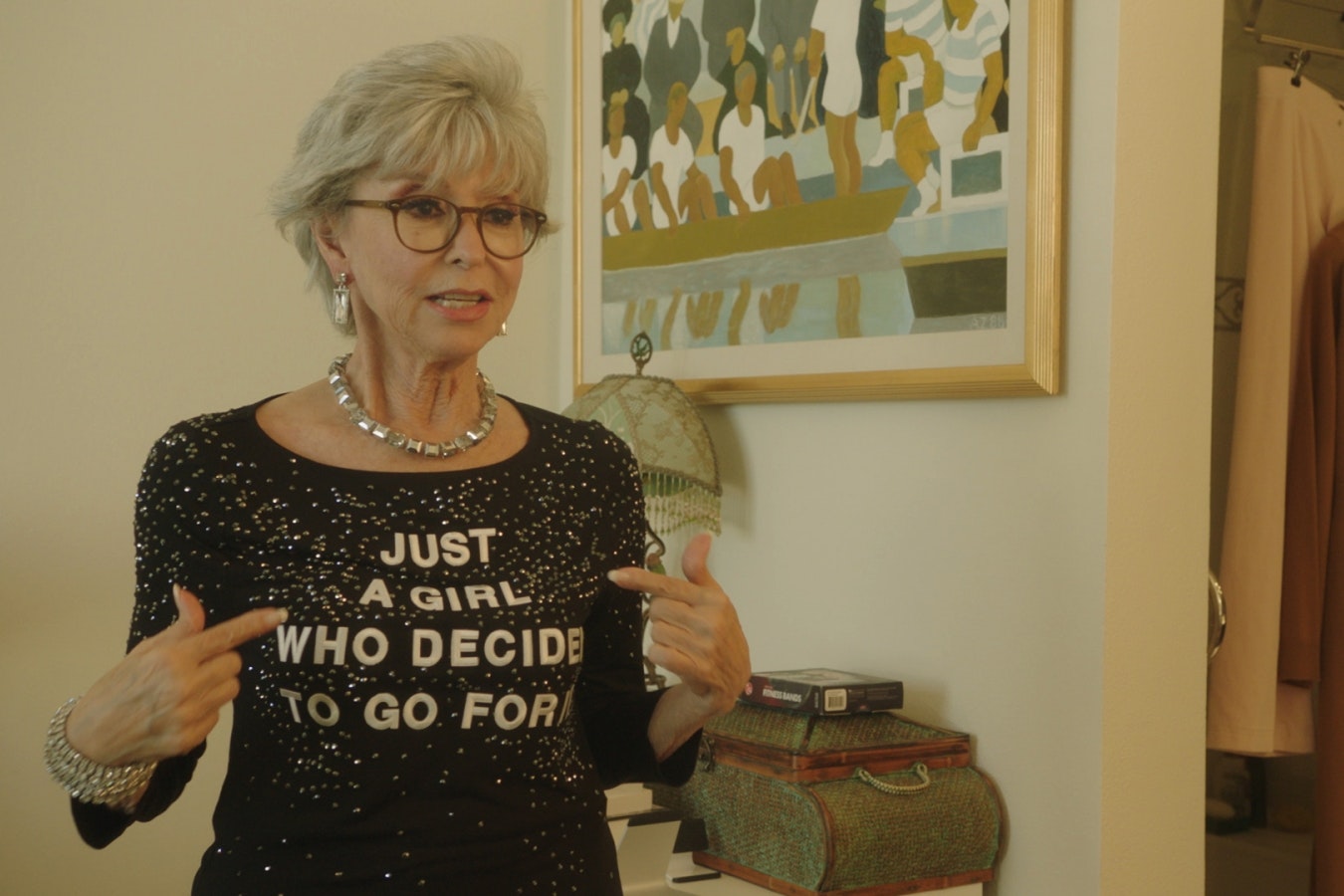

Film scores can do a variety of things at any given moment, but their primary function is to serve the narrative. Whether it’s in feature films like the award-winning Clemency or in documentaries of larger-than-life figures like Toni Morrison or Rita Moreno, Kathryn Bostic’s music is always essential without ever being distracting.

That’s a tricky line to tread, and when we sat down with the self-described “less-is-more” composer over Zoom recently to talk about her upcoming work - including documentaries of Amy Tan, Rita Moreno, and Black artists in Black Art: In the Absence of Light - we discussed everything from developing trust with directors to being one of the few Black women working in the industry today. Oh, and we geeked out over Thomas Newman too.

When did it click for you that composing is something that you wanted to do and wanted to pursue?

You know, it’s funny when people ask me that question. I think I literally was just born this way. My mother was a classical pianist and composer herself, and she used to teach piano. She went into labour with me when she was teaching a piano lesson. So I really think I just came out into the world with this desire to be a musical storyteller. The piano was my first instrument, and I always appreciated how it made me feel when I would hear her play or hear other people play. And that sensory connection would then guide me to the piano to create my own little song.

I started playing when I was very young. It was just something I instinctively gravitated towards. I didn’t even think about it as composing! I just was making up these little ideas and songs and playing around and improvising. But in terms of actual film scoring, I started writing music for regional theatre and I did some Broadway work, and that led to this curiosity about creating music for multiple platforms. But fundamentally, I’ve always enjoyed music as a form of storytelling. So I think I look more at composing as sonic storytelling, or sonic dictation. Because when you’re writing music you’re really accessing a very extraordinary frequency of creativity. And when you get out of the way and allow that access to be a part of that journey of storytelling it’s remarkable.

Your filmography has a lot of great documentaries in it. What is it about scoring for that type of film that you really love?

With documentaries, there is this hands-on, in-person connection with the topic. I’ve primarily done documentaries about people, rather than places and circumstances, I find that kind of one-on-one dynamic with them - whether I’ve met them or not - fascinating and inspiring. But all film scoring... it’s different, but it’s the same. ‘Cause, you’re there to help create a sonic arc that will carry the scene and translate the emotion that the film dictates and that the director wants.

When you have people that want you to work and be of service to their vision, it’s a very high honour for me.

What was it about Amy Tan’s story that made you want to score it?

A lot of different things inspired me to be a part of that film. But mainly it was the graciousness and the vision of the director, James Redford. I had worked with him on his previous film and he had reached out to me through his producers and that team around him. He was such an exquisite and gracious person to collaborate with. He really has an appreciation for the people who are on his team showing up with what they do and letting them do that.

You said that you’ve worked with James Redford before. What was it about working with him on that previous project that served you well in this project?

I worked on his film, Playing For Keeps, which is a fabulous movie about adults needing to know and when to take time out from the routine and the arduousness of their work and how to relieve that stress. So he profiled different people who shared what their hobbies were and what brought them joy. He’s a very — I talk about him in the present tense because to me he’s still very much here. In fact, I could feel him throughout my scoring of the Amy Tan documentary. I literally was flooded with goosebumps the entire time. He was a musician himself, so he really appreciated that aspect of storytelling.

I got to write some old-school kind of funk and R&B that you skate to. Then one of his other scenes was with these adults who participated in this massive go-kart race all up and down these hills in San Francisco, so I got to do some Rock ‘N Roll for that. It’s very rare that you have a director go okay, she’s got it, I really don’t need to interfere with her process. I completely trust her.

When the Amy Tan documentary presented itself, a large part of that narrative is piano. They knew that I’m a pianist and that I had studied both classical and I can play jazz. I’m an artist. That trust enabled me to move very quickly and unfettered by constant scrutiny and judgment.

I assume that when somebody offers you a Rita Moreno film, that’s a very hard thing to turn down...

Yeah. I mean, she’s Rita Moreno. I don’t like to take on too much when I’m writing, because it’s a very all-consuming process. But it’s Rita Moreno. And by the time I sort of regained my senses, it was a no-brainer. They wanted a Jazz score because she loves Jazz. And the director [Mariem Perez]...she and I really hit it off. Her process is very, very organic. She doesn’t speak in terms of music, which I told her was actually fine. I actually prefer when the language of music and musical terms is not used so readily. Because sometimes they’ll say things and it has nothing to do with some of the phrases they’re saying. But Mariem and I were able to create trust in our process. I think that’s the biggest thing as a film composer. You want whoever is helming the ship to know that you’re gonna be able to deliver their vision and that you’re gonna bring something unique to that.

Rita Moreno is such a force. She is just one of the most resilient and honestly self-aware people I’ve ever met. She has no trepidation. And for me, that is…that’s such another huge way to be informed creatively about the kind of score. I mean, she showed all her weakness—she showed all her vulnerability and she showed the strength through that vulnerability. So that was inspiring.

I’m guessing that one of the joys of doing a documentary is that you’re switching between styles quite often. You’re marking different phases of your subject’s life, so it can almost feel like you’re scoring five or six mini-films within one film. What percentage of that is a fun challenge and how much of a percentage of that is daunting?

I think it goes to the premise that music for me is a conversation. When you’re talking you have moments that are perhaps very sparse and laidback. Then you have moments that are very animated and excitable, moments where you’re just listening and there’s silence. So it’s very nuanced. A feature film is also the same way for me. It can be very much the same. When I wrote the score for Chinonye Chukwu’s film, Clemency, that was a very, very sparse kind of conversation. And therefore that was that palette.

There’s a track called Birthday Celebrations on the Rita Moreno doc, which I absolutely love. It feels like it fits perfectly for that time period. And you feel like you’re really having fun with that track in particular. It sounds very different from anything else in the score.

Yes, it’s true. Because that’s how the film opens. I think she was celebrating her 87th birthday party, and so we wanted to set that tone right away. The rest of the film deals with some very complex and dark issues of abuse and systemic racism, and the way in which the Hollywood film industry at that time and even to some extent now deals with women and what she had to go through. So that’s why there’s that contrast.

In a documentary, there’s more of an emphasis on the footage, and telling the story through interviews and other means. Do you have conversations with the director about how prevalent your score should be in the overall mix?

Oh, absolutely. I always try to pay attention to that dialogue, because it requires crafting the music so that you’re framing the conversation, you’re framing the exposé without getting in the way of it, and without making it about your music being the narrative. I mean, it’s interesting you bring that up because I’m kind of a less is more kind of composer in many ways.

For instance, when I scored the Toni Morrison documentary, her voice and her commanding beingness is so strong. It’s just monumental. I really didn’t want to put a lot of music in it at all. Sometimes me and the director will talk about a scene and we’ll talk about the intention and maybe the orchestration and the emotional quality, so then I’ll give them a menu of different options and different things. I’ll say, well here’s the full mix, but you may just want to use this particular element out of that mix. You may just want to strip it down and use this, that, and the other and the director of the Toni Morrison documentary said, oh no, we want all of your music in there. They thought it really served the narrative. And I was actually quite frankly surprised.

A number of composers I’ve talked to have spoken of the importance of making sure their scores as a whole can be listened to and enjoyed outside of the project it’s attached to. Is that something you think about when you’re composing?

I do and I don’t. I try not to get too far ahead about how the score is going to work on its own because I’m really trying to craft the story of the film. When I put the score together for my soundtrack release, I don’t necessarily put every cue in because some of the cues are minimal. It’s what I thought reflected the overall tone and energy of the scores.

There is racism. Have I experienced it? Absolutely. There is sexism. Have I experienced it? Absolutely.

In reading some of your previous interviews I’ve noticed that you come onto certain projects at different times in the process. I’m curious to know what sparks your creativity the most? Can you go off the script alone? Do you prefer seeing a full film? Do you prefer just having a conversation with the director and going off that?

All of those things you mentioned absolutely inform me creatively and spark something. I think sometimes I’m asked to create themes prior to seeing the footage, so the director can have something to cut to. But when I see that footage and when I see what the actors are putting forth, when I’m tapping into that essence of their own emotional content for that scene and when I’m seeing the environment of the film, that always brings about a very different overview for me.

I often look at the script beforehand just to look over what is involved. But then once I see the footage...for instance, the Toni Morrison documentary that opened with us just hearing her voice, and that was just incredible in terms of hearing it as an instrument. And then they cut that open with a serious beat. They cut it with this swagger, and all of a sudden I could just feel her. Her swagger and her bravado and her down to earthiness coming into a room. And I wanted to honour that. I wanted to frame that with simplicity. I didn’t want to do this lush underscoring on her voice. I just wanted to frame it with people-like conversations. I chose those pizzicato strings and little flavours of Blues like someone has come in the room and you know you better be paying attention. And then you might hear little flavours of response. And that’s how I wanted to do that opening. The more information I can have the better.

You are also an artist in your own right as you mentioned. When you are working on your own project at the same time as you’re working on a film or a documentary, do you develop certain strategies to get into certain mindsets for the simultaneous projects?

I think you absolutely have to get in a different mindset because you’re working on something different. I don’t try to overthink everything. I don’t try to get too far ahead of the unfolding of things. You just have to be present. You have to be present and say, okay, right now the task at hand is this. And what does that mean? For instance, I’m the artist of residence at the Chicago Sinfonietta and they wanted me to create a piece about the common ground of humanity. They were doing what they call a pairing. And they said, we want to put you with Aaron Copland’s Fanfare For a Common Man, so we want you to do a brass choir that deals with humanity. And I didn’t want to think too much about Aaron Copland. He’s one of my favorite composers, and that piece that they mentioned is one of my favorites. But I didn’t want to get distracted by that. So I just started thinking about that journey of humanity. So in other words, you’re given information and a theme either as a result of your own choice or somebody telling you what they want. I call it marinating the vibe. You marinate the vibe.

There’s a lack of diversity and a lack of female composers in the industry. First of all, why do you think that is and what do you think the industry can do to improve that going forward?

A lot of it has to do with perception and the way in which people are informed by perception. You have very strong elements that dictate illusions, and I say that word very strongly. Illusions of hierarchy based on gender, skin colour, age, culture, ethnicity, religion. So there’s been a way in which we’ve all been misguided in terms of how to attain our true potential and the ability by which we forget that this is our birthright. It’s our birthright to excel and to reach for the sky and beyond. I think things are beginning to change now because we’re at such a tipping point on every level of our consciousness. My friends tease me ‘cause I had to find some levity in this craziness. So I call this time our cosmic colonoscopy.

I think the keyword is autonomy. As an artist, I reside in that ability to be creative. Therefore to create my life and therefore to create the terms by which I live. And those terms transcend boxes. I’m ever aware of it and cognizant of it when I’m creating because when you’re creating music to access that kind of place and that frequency, there’s no room for these types of terms and definitions. Because I’m accessing something that’s very pure. So it’s taught me how to look at life, and it’s taught me how to live. And it’s taught me to see how so much of who we are or how we’re defined is constructed. I’ve been taught to have no control over those constructs. And I decided no, I absolutely have control because it’s my life, and therefore it’s my narrative. So that’s my take on it.

I definitely think things are getting better, for women and for people who are underrepresented in our industry. Mainly Brown skin and Black-skinned people. But I think there’s a long way to go because there’s still a tendency for compartmentalization. Oh, you’re the African American composer, so you’re gonna do African American films. It’s very easy for the traditional presentation of being a composer, which is primarily white males. And I think we all have to just really ask ourselves, what’s important in life? And what’s important for me is being curious and not being hemmed in by these constructed ways of perception.

How cognizant are you of being one of the few Black women in this side of the industry working as often as you are? Do you get many people, Black women or Black men reaching out to you asking for advice on how to get into the industry?

Yes, I do. I’m happy to be able to be of service within my community of African American composers and musicians and people in general who feel they’re underrepresented and want to have an idea of how to go about pursuing a career in film scoring. What I try to do is demystify even the question itself. I think so much about what life is that we’re taught about, what’s difficult to achieve, and what’s difficult to be, whether it's because of your gender or your race. And granted, these are very real, real issues and dynamics. I’m not being dismissive, there is racism. Have I experienced it? Absolutely. There is sexism. Have I experienced it? Absolutely.

I don’t want to become so encapsulated in that way of interacting that I lose sight of the purpose and the power of my own autonomy irrespective of that. This whole notion that, oh, you have to try harder… if I let that be a dominant mindset in the way I navigate my life, then I’ve already abandoned who I really am.

I’m happy to be able to be of service within my community of African American composers & musicians, and people in general who feel they’re underrepresented.

What’s on your bucket list to compose for?

Oh, I would love to do an epic action movie as well as an epic dramatic feature. That would be amazing to score. Something where I could have this orchestral panorama of music, this orchestral instrumentation as well as cultural and ethnic instrumentation. There's so much that I want to do. And my biggest thing is I’m not gonna wait for someone to give me that permission. I’m just gonna go ahead and do it. And that’s why I do these other platforms. I love the fact that I’m able to work with orchestras and I’m able to then turn around and work with a group of musicians. I just finished the record of my songs with this incredible group of musicians.

Your bucket list is your life. Just jump in and do it. Get it done.