Words by Anton Spice

In another life, Sarah Davachi says she might have been a pop producer. While this may surprise people familiar with the LA-based composer’s glacial compositions – less so those who listen to her wide-ranging NTS Radio show - Davachi’s fascination with sonic texture and depth transcends genre. “In my own music it unfolds in a very different way to how pop music does,” she tells me over video call, “but I can appreciate those layers and that sense of when things come and go, whether it's a 3-minute piece or a 3-hour one”.

This temporality is central to Davachi’s work. There is a precision to the compositional decisions she makes, a rationale for the structural framework of each piece, and fastidious control of the tonal and textural changes she employs. Without getting lost in the problem of time itself, it’s worth saying that Davachi’s music errs towards the relative. That Two Sisters is her sixth LP in four years speaks very much to this approach. She enjoys the restrictions of the album format but has freed herself from the demand to make finite statements. Iteration is not the means to an end but an end in itself.

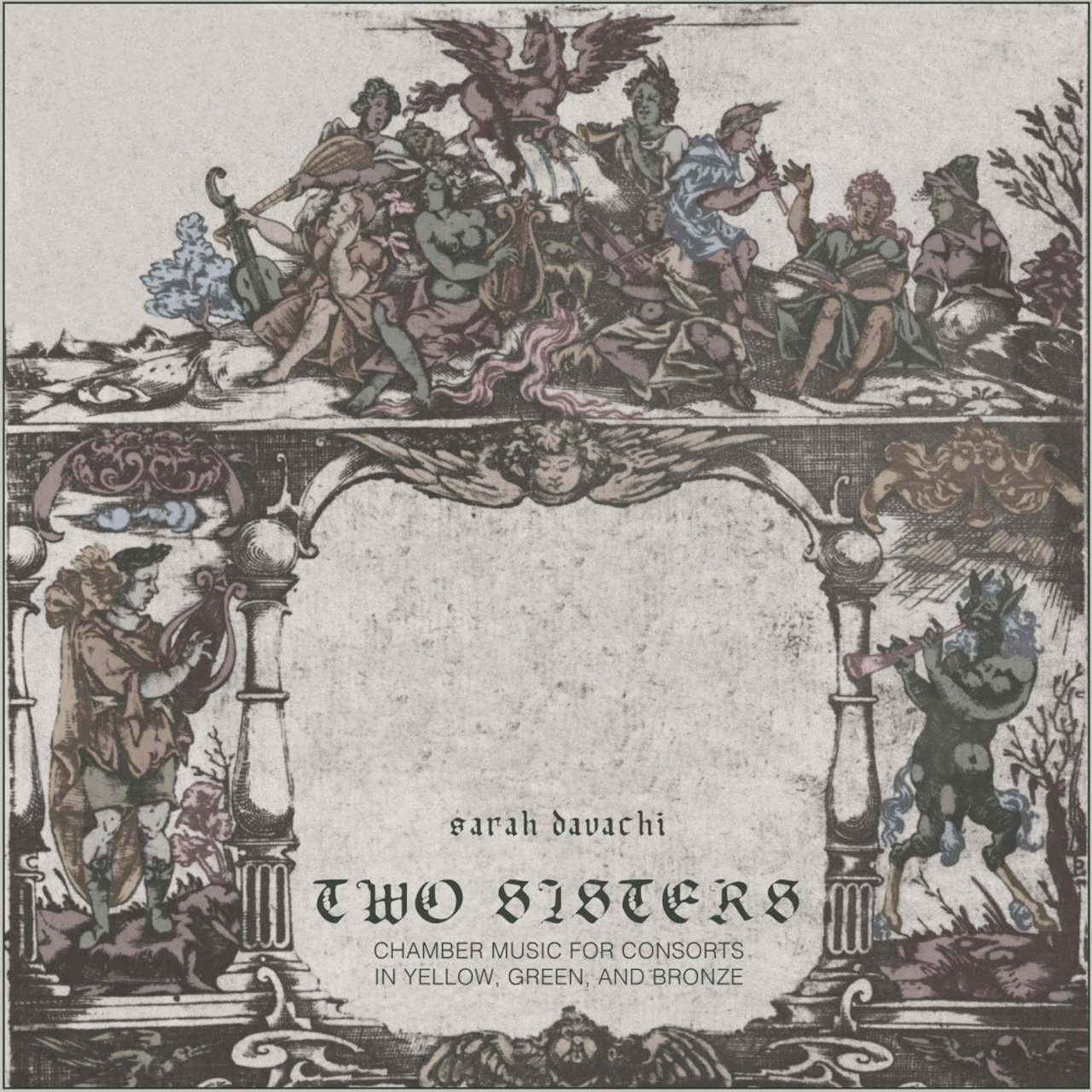

Released on her label Late Music - itself a kind of temporal pun on the chamber music she writes - Two Sisters makes a conscious effort to bring together the worlds of electro-acoustic and live performance composition. Davachi has, in recent years, become a formidable presence in both contexts, touring alongside the likes of Grouper, Ellen Arkbro and William Basinski, and composing for the London Contemporary Orchestra.

When I'm working on a record, the direction that I want to go in afterwards is always to do things on a bigger scale.

Woven into a fabric of sine tones and drones, Two Sisters features writing for string quartet, choir, woodwinds and trombone. Informed by an ongoing PhD in musicology, Davachi also challenges herself to learn and incorporate new instrumental idioms into each work, and here it is the carillon - rig of cast-iron church bells played on a keyboard - which takes centre stage. Performed by Tiffany Ng, it holds Two Sisters in a balanced state between the sombre overture and ceremonial encore. This particular carillon is thought to be the third largest in the world and is joined on the album by a rare Italian pipe organ dating back to 1742. Both are instruments whose socio-cultural connotations Davachi is excited to prise from their ecclesiastical pasts.

To tune into Davachi’s work then is to refresh the practice of listening itself. It is to hear bells without hearing “The Church”, to hear early 18th century organs without hearing “Baroque”, or the Mellotron without hearing “Progressive Rock”. Labels like drone, minimalism and the truly unholy modern classical are brushes too broad to paint the lines her music draws. Instead, in words Pauline Oliveros might enjoy, we are invited to listen to Davachi’s listening, and experience tempo, tuning and harmony on her terms. Just as one might do a pop producer.

It’s only just been released, but have you had time to process your thoughts about Two Sisters yet?

Yeah, a little bit. The way that I work is having projects overlap, so the things that I’m giving my full attention to right now are things I was still working on in the background when I was working on Two Sisters. When I'm working on a record, the direction that I want to go in afterwards is always to do things on a bigger scale, on a longer scale. It's hard because I make records, and there is obviously a limitation of what I can do, but I feel that with every record I'm trying to see how I can do the same sorts of things that I was interested in but just on a different kind of scale. Having that space from it makes me think I wish this was longer or I wish this was happening slower.

In that sense, it sounds like the records are just like way-markers on what's otherwise a longer trajectory of ideas.

Yeah, that's how I think of it, and to me, that's just a really intuitive way to think about making music. I know it's cheesy to put it this way but it's part of the journey, it's the long game. I feel like it's the kind of thing that you’re always moving closer towards, but the point is not necessarily to get there, it's to keep figuring it out and working on it. It's strange when I read reviews and I hear people mention in a pejorative way that this person is repeating the same thing or doing this thing that they already did before. It's like “well, yeah - why would you do one thing and then never do it again?” If that's interesting to you, why wouldn't you keep exploring that? Who just does one thing and then never touches it ever again? I don't understand that mentality.

I come from a more electro-acoustic background where I have no problem recording something and then chopping it up.

The same could be said for music history, where the repetition of an idea which was explored say thirty years ago is often thought of as pejorative, instead of as looking at that idea from a different perspective. In using instruments from a relatively long time ago, it feels like you're already engaging in a kind of cross-epochal conversation.

I feel like there is a lot one could say about that topic. Instruments are objects that come from a specific time. They existed in the way that they did, emerged in the way that they did, because of the time that they were in and because of the demands of the music at that time. They are still very much of a time, but I think it's unfair to connect instruments so specifically to those times. Once they're created, I don’t see any reason why they're not just there for people to use at any point in time. I use a lot of instruments from different centuries, but I also use instruments like the Mellotron, which was stuck in the '60s and '70s for a long time, but there's no reason for it. You don’t need to make pastiche music, it doesn’t need to sound like it did then, it's just an instrument, it's just a tool for making sound. Anybody without the context of what it was known for can use it to do something interesting, and I don't see why we should deny that of the instrument.

I suppose instruments like organs or church bells have such evocative connotations, and so much cultural baggage in their sound, that they are harder to abstract than other instruments. Is there an element for you of playing with or subverting the meanings inherent in some of those instruments?

I feel like there isn’t exactly an easy answer for that one. For me, it's kind of different because I grew up very secular, so those kinds of sounds were never attached to anything personally positive or negative for me. But obviously, I understand that that's not the case for most people. I don’t think it's as simple as saying the more we use the church organ the more it's going to remove it from its church association. I think maybe bringing those instruments outside of the church, physically, is helpful, at least in my experience. I wish it were as easy to say, “well, we'll just use them in non-sacred music and that'll remove hundreds and hundreds of years of association”, but it doesn't work like that.

The carillon is an interesting example of that, not only because it is physically outside, but because it seems to straddle both the sacred and the secular. How do you begin to go about composing for it?

I'm a keyboard player so I feel like I intuitively understand certain things about keyboard instruments, and I feel pretty comfortable writing with them. But what's interesting for me is that the keyboard is just an interface, it's just a way of selecting pitches, it's not really anything to do with the instrument, so it's always interesting to me how different keyboard instruments are. Learning about the carillon from Tiffany Ng, [resident carillonist at the University of Michigan], one of the tricks that she told me for writing a piece for the carillon is you need to try to play it on a piano using just your index and your middle fingers because that sort of imitates the scale at which you’re moving your arms and your legs when it's played on the carillon. Stuff like that is an interesting way to think about this connection between the physicality of performing something because I come from a more electro-acoustic background where I have no problem recording something and then chopping it up and turning it into something that isn't even performable.

On Two Sisters, the carillon appears in the first track and then at the very end, creating a sense of symmetry or circularity to the structure of the album. Did you compose the record as a whole rather than as a series of individual pieces?

I'm the kind of person who likes making albums, I like thinking conceptually of albums as these self-contained things. It's something I tend to do on all records, but with this one specifically, I did make an outline for it before I did any of the writing or recording. Even in those early stages, I was thinking of it almost as these mirror images of different moments on the album, having it be this balanced thing. Conceptually it doesn’t mean anything more than that to me, but aesthetically and in terms of the listening experience it was something that I was interested in adhering to. I can have my idea of what I wanted to get out of it, but I very much don’t want to put that into anybody else's head. I don’t want somebody listening to it with some idea of what it's supposed to mean or where it's supposed to go, other than maybe from these broad conceptual markers.

I think the most ideal way to work is to be able to do it in a residency format where you can come up with a piece and then workshop it.

You spoke about enjoying composing within the confines of the album format, and I wanted to ask how you begin to convey a sense of temporality within such a specific amount of time? It often feels as if you're pulling in a slightly different direction to linear time. In some music, it passes very quickly and in others, it feels much slower.

The latter is definitely something that I think about when I'm writing. The way some people would like writing lyrics I just enjoy playing with that sense of pacing, and it's something that I think I've honed pretty well through my live performances. I have a pretty good sense of how things need to pass with time and when things need to be slower and faster. I've made concerted efforts to distil that and balance that between the recorded music and the live music. I like being able to manipulate things to a controlled degree, I like being able to take a sound and be like “that should be two seconds shorter, or five-second longer” - to be able to really be sculptural about the sound when I'm working it out for an album. Being able to do this back and forth helps me be able to get that sense of time.

Are there different compositional methods that you employ to create a sense of time in the music? It sounds as if listening is actually part of your compositional process.

Yeah, it's a huge part. When I'm working on records specifically there is just so much listening. I think that's why I gravitated to this more electro-acoustic way of working with records. When I work with ensembles, I think the most ideal way to work is to be able to do it in a residency format where you can come up with a piece and then workshop it, back and forth. To constantly listen to something and have people play it and hear it is so critical to me. I can't just write something, have it performed and then be like “that's it, it's done”. When I work alone or on records, I necessarily build that into the process because I don’t know how to do it any other way.